The Jöttkandt Effect:

Reading

Nabokov Imaginatively

The Nabokov Effect: Reading in the Endgame. Sigi Jöttkandt. London: Open Humanities Press, 2024. Pp. 192 (paper).

Reviewed by David Potter, University of Sydney

So what is the Nabokov Effect? The Nabokov Effect is both the title of a book and an idiosyncratic phenomenon which that book describes. On the first:

The Nabokov Effect centres on […] letteral events. It contends that if a “controlling presence” is operative in Nabokov, it will be as something that oversees the collapse of authorial paradigms and the metaphysics of the self these paradigms sustain. Linear logics, causality, teleology, the levers of literary narrative turn out to be no match for a certain non-intentional agency masquerading as a designing author’s style.[1]

Great, okay, so Jöttkandt is playing what I wish Nabokov scholars would start calling “The Wood Maneuver.” The idea is to sort of “knight’s move” oneself out of having to abide by the historical Nabokov’s cutting strictures about how to read his fiction. The first place I saw someone do this was The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction (1994), where Michael Wood argues that the version of Nabokov we find in interviews is “too self-sufficient, too armoured against doubt” to be the full story. Wood starts his book with a brief summary of a historical writer’s life, a writer he calls “V.” While the facts of V’s life are identical to Nabokov’s, this is a different guy:

I am guessing about the mentality behind the facts, and I don’t want to hide the guesswork. I call the man V not to deny his connection to the historical Nabokov, but to refuse too narrow and inflexible and immediate a connection, and to leave room for others. This V is my Nabokov, if you like; or one of my Nabokovs; I’ll call him Nabokov from now on. But I do also want to suggest that this life itself really is a sort of fable, as all achieved careers are: exemplary, purified, haunting.[2]

The reason I say Jöttkandt is playing The Wood Maneuver is because she starts in pretty much the same place:

The “Vladimir Nabokov” of The Nabokov Effect cannot be traced back to any author or subject that precedes it but emerges rather as the name for a fundamental dystropia, a swirling VN vortex into which all the constructions of identity, subjectivity and authorship as the products of letters and inscriptions are toppled and engulfed. (39)

Same move, different words.

It is worth noting that on occasion Nabokov used to engage in this kind of narratological doubling in his real life. Here he uses his own initials as a signature to “sign” his way out of a particularly probing interview question:

Magic, sleight-of-hand, and other tricks have played quite a role in your fiction. Are they for amusement or do they serve yet another purpose?

Deception is practiced even more beautifully by that other V.N., Visible Nature. […] In art, an individual style is essentially as futile and as organic as a fata morgana. […] A grateful spectator is content to applaud the grace with which the masked performer melts into Nature’s background.[3]

Okay Nabokov, but the only “Visible Nature” that’s actually visible from inside one of your books originally emanated from that other other V.N.: you. The author doesn’t just fade into the background here: he is the background. A book’s Nature is its author’s nature, a dynamic which Robert Alter described well:

Is it possible that through this utterly different figure Nabokov is probing the dark underside of his own vocation as a novelist inventing worlds? […] The oddly paired destinies he imagines in Kinbote and Shade, together with the intricate artifice through which they are represented, reach toward a serious visionary glimpse of order behind seeming arbitrary chaos, pattern implicit even in what looks like random destruction, and a luminous prospect beyond the feared blackness of nothing fading into nothing. In these respects, the two fictional figures are flesh of his flesh.[4]

That sounds like Nabokov alright: “a luminous prospect beyond the feared blackness of nothing fading into nothing,” the prospect that nothing fades instead into something. For all his tricks, Nabokov always remained rather hopeful about things like life after death and the godliness of creativity. This is from one of his lectures, “The Art of Literature and Commonsense”:

That human life is but a first installment of the serial soul and that one’s individual secret is not lost in the process of earthly dissolution, becomes something more than an optimistic conjecture, and even more than a matter of religious faith, when we remember that only commonsense rules immortality out. A creative writer, creative in the particular sense I am attempting to convey, cannot help feeling that in his rejecting the world of the matter-of-fact, in his taking sides with the irrational, the illogical, the inexplicable, and the fundamentally good, he is performing something similar in a rudimentary way to what [two pages missing] under the cloudy skies of gray Venus.[5]

I wish that that bracketed part at the end were a stylistic affectation of either mine or Nabokov’s, but we are indeed missing two pages of the manuscript here. It certainly looks like he was about to say that a creative writer performs something “similar in a rudimentary way to” God or Nature. In any case, the way the published version reads is accidentally rather comical, as if Nabokov was struck down by a bolt of lightning before he could finish what he was saying. The “[two pages missing]” is like a “technical difficulties” card going up. And when we finally get the livefeed back, it’s pointed straight up at a cloudy sky and there are muffled screams coming from off-camera. Also we’re on Venus for some reason.

Michael Wood split the authorial atom we call Vladimir Nabokov into his “four major or most frequent meanings”:

1) the historical person whose life has been impeccably told by his biographer Brian Boyd, and whom I glance at occasionally here, but who is not my principal subject.

2) a set (also historical) of attitudes, prejudices, habits, remarks, performances which is highly visible, highly stylized, and which I find dull and narrow, and having almost nothing to do with the writing I admire: Nabokov the mandarin.

3) a (real) person I guess at but who keeps himself pretty well hidden: he is not only tender and observant but also diffident, even scared, worried about almost everything the mandarin so airily dismisses. I would think this person was a sentimental invention of my own if Nabokov’s texts were not demonstrably so full of him, and if I had any reason to invent him. Given the choice I would prefer another Nabokov in his place—someone less predictably the obverse of the haughty public presence. This diffident, doubting person is the one I think of most often as the author in Barthes’ later sense: the textual revenant rather than the face on the dustjacket.

4) identifiable habit of writing and narrating: mannered, intricate, alliterative, allusive, perverse, hilarious, lyrical, sombre, nostalgic, kindly, frivolous, passionate, cruel, cold, stupid, magical, precise, philosophical and unforgettable. Particular clusters of these characteristics are what we identify as Nabokov the author […], the performance on the sheets of paper.[6]

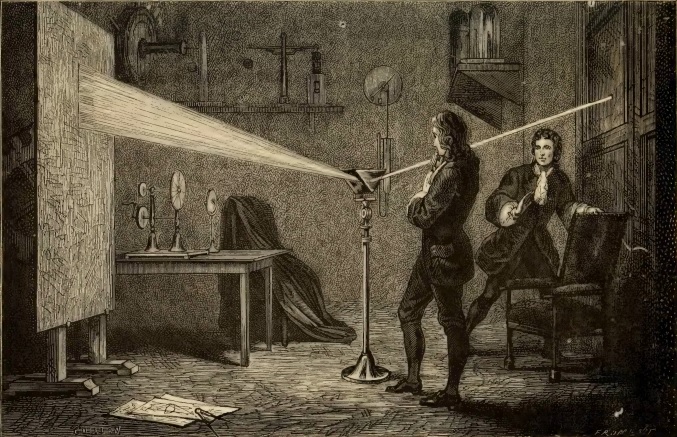

Imagine what Wood’s doing here as holding a certain kind of translucent crystal up to a beam of light. The crystal splits the beam into four differently colour-graded cartoon Nabokovs, each with its own agenda. It is by such means and measures that Isaac Newton first refracted a beam of white light through a prism to project a cross-section of the colour spectrum onto a blank screen, as seen below:

“Newton décompose la lumière au moyen du prisme,” in Louis Figuier, Vies des Savants Illustres du XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: A. Lecroix, Verboeckhoven & Co., 1870), between 30 and 31.

Arguably, cinema began here.

While undeniably brilliant, the Nabokov we meet in essays, lectures, and interviews is also stern, professorial, truculent, and extremely fickle. Obeying all his orders at once, even if you want to, is exhausting and not always possible (and that’s without even mentioning all the times he gives contradictory answers, or when he flat-out trolls). These days we take this Nabokov, Wood’s second, with a grain of salt. It’s not that this Nabokov necessarily misrepresented himself in these settings; it’s more that he was over-protective of his own spontaneity. It’s common knowledge that on almost every occasion where he agreed to an interview, Nabokov would dodge the experience of being probed in person every other day by requesting interview questions in advance, composing his answers overnight, and leaving the finished product at the front desk in the morning, sometimes without even meeting his interviewer face-to-face. If it was a filmed interview, he would do exactly the same thing, and then simply read his pre-prepared answers out from an off-camera cheat sheet. The Nabokov I’ve come to know in the archives could be warm and gregarious in company, but extremely guarded when it came to outsiders like journalists and film-directors. Anyone picking up Strong Opinions (1972) for the first time today would naturally assume Nabokov was an uncommonly smooth, erudite interview-subject, when he was in fact the exact opposite. That book is a kind of stitched-together “Greatest Hits of My Favourite Interviews” prepared and edited by Nabokov himself. Yes, all its pieces come from real published interviews; and no, he didn’t leave them alone.

Wood’s four differently-graded Vladimir Nabokovs are each well-observed and well-described, but that’s not really the part of Wood’s approach that caught on. No-one in Nabokov scholarship has ever started a conference presentation by saying: “You know, it’s the third Wood-Nabokov that intrigues me.” And this quirky post-Barthesian mischief wasn’t all about combatively riling up perceived traditionalists. The real appeal was in the freedom: freedom to read these books without having to want yourself to care what Nabokov himself might have made of you.

The real Nabokov died in 1977, and he’s buried in Montreux next to Véra, his wife, and Dmitri, their son. He designed his books to have a whole lot of complicated circuitry that’s still being worked out to this day, and then he went spectral on the point of death. Now our dealings are with his ghost. Nabokov scholars have been in an abusive relationship with his ghost ever since. Eric Naiman described this state of affairs extremely well in Nabokov, Perversely (2010):

In Nabokov studies […] readers [are] in an interpretive dilemma—they have to read imaginatively but not preposterously, without common sense and with it. They want to find things in the text but fear finding too much. A yearning for identity with the master has two faces: the desire to dazzle and the fear of seeming ridiculous or crude. The text simultaneously tempts the interpreter and threatens to expose him. With a little etymological license, one might call this state of affairs hermophobia. It encompasses a number of responses, including excessive caution, a fear of exposure, shame, and self-protecting (and, thus, self-intimidating) attacks on the interpretive excesses of others. […] [T]his condition is common to readers of Nabokov; it is the state of affairs that Nabokov’s oeuvre works incessantly to produce.[7]

We are to read more insubordinately, then, remembering one of our protagonist Adam Krug’s many somewhat over-enlightened sermons in Bend Sinister (1947): “There can be no submission—because the very fact of our discussing these matters implies curiosity, and curiosity in its turn is insubordination in its purest form.”[8] So we follow Nabokov’s lead by not following his orders, if you follow my drift. Adopting a critical position like this isn’t intended as a denigration of the historical Nabokov at all. Readers like Wood, Naiman, and Jöttkandt aren’t turning their back on that Nabokov; they’re just calling his bluff a little bit. This is the background to the approach described in Jöttkandt’s back-page blurb, the part about “suspend[ing] the long-held critical investment in Nabokov’s authorial control to focus on another principle of representational agency making incursions into his books.” A worthy goal, and one I share. And Wood shares, and Naiman shares, and Will Norman shares, and Jacqueline Hamrit shares, and Siggy Frank shares, etc. I point this out less as a stern and/or specific criticism of Jöttkandt, and more to demonstrate how good her company is in these literary-theoretical trenches we inhabit alongside other scholars (whether we want to or not). I also want to reassure any future students of Nabokov who might be reading this to look around and be reassured: any absolute claim the historical Nabokov may once have held over how to read his fiction has been well-and-truly suspended circa 2024. Read him however you think is best: no behaving yourselves.

The interesting thing about this kind of critical liberation from our abusive relationship with Nabokov’s ghost is that every single one of these “oh-so-playful, oh-so-insubordinate” readers—(and I include myself here)—always ends up crawling right back, again and again, to those transcendently rich books with the big letters on the front that spell out Vladimir Nabokov’s name and nobody else’s. Even despite ourselves, that seems to be the way we like it. Look what Michael Wood did: he took one Nabokov and made four. Then he took the idea that you could only argue for one reading of one novel at a time, and he argued for “not so much meaning as a set of possibilities of meaning,”[9] broadening the scope of critical activity by at least one more dimension (possibly more). Do these sound like the actions of someone who wants less Nabokov in his life, or more?

Roland Barthes didn’t kill the author; he abducted the author for his own nefarious purposes:

As institution, the author is dead: his civil status, his biographical person have disappeared; dispossessed, they no longer exercise over his work the formidable paternity whose account literary history, teaching, and public opinion had the responsibility of establishing and renewing; but in the text, in a way, I desire the author: I need his figure (which is neither his representation nor his projection), as he needs mine (except to “prattle”).[10]

In any context other than literary theory, these words would read like the testimony of some deranged stalker-murderer (or one of Nabokov’s protagonists). But Barthes is right: we are this obsessed; we are this beholden to our author, at the end of the day, especially those of us who make a habit of writing more than one thing about him. I might not believe absolutely everything Nabokov says in his interviews, but that doesn’t mean I don’t still obsess over his every word. Who on earth wants their favourite authors to only tell the truth? Where’s the fun in that? What of beautiful deceptions and splendid insincerities? Who else has that in such plentiful spades as Nabokov?

Modern readers like to imagine ourselves as free, and yet here we all are back again, still reading and writing about people like Nabokov. After all these years, and all our most timely and radical ideas about reading this guy “differently” now—“now,” always now, at this one specific juncture in time, every time—after all this time he still has us exactly where he wants us: he’s the dom; we’re his subs. And Nabokov critics accept this as the price of doing business, especially repeat offenders (however insubordinate). Nabokov’s ghost will always haunt us: our task is to find ways to make this work to our advantage. Jöttkandt excels at this.

Spectral Nabokov

The longer we are haunted by this textual ghost, the stranger and more mannered the actual hauntings get and the more we as critics start to haunt him back. The textual Nabokov we’re chasing is partly our creation. We as his most persistently obsessive readers all collectively hallucinate him, in a way: we desired our author so much, we made our own. Nabokov has become a ghost in the machine, a photographer’s shadow, an interference pattern. I’ll call this hallucination the spectral Nabokov from now on.

This spectral Nabokov is like a blend of all Wood’s Nabokovs in one, so imagine again that “Nabokov spectrum” which we had Isaac Newton project for us, except now with time running in reverse: so, the four differently-coloured Nabokovs leap up off the page, back through the refractive crystal, and into our world. Also, we made him up. I reckon Wood was already talking about him, actually; he just didn’t give him a number. This is the Nabokov he calls his Nabokov: “This V is my Nabokov, if you like; or one of my Nabokovs; I’ll call him Nabokov from now on.”[11]

Given how close they are in spirit, I’m a bit surprised to find Wood isn’t mentioned in Jöttkandt’s book. They would be excellent to read together. Jöttkandt is also a great choice for anyone looking to bridge the gap between Nabokov and continental theory, very much like Jacqueline Hamrit’s two books Authorship in Nabokov’s Prefaces (2014) and Deconstructing Lolita (2022).

Jöttkandt’s first book was Acting Beautifully: Henry James and the Ethical Aesthetic (2005). One of the highlights of The Nabokov Effect is its discussion of stream of consciousness in relation to both Henry and William James. Aside from the Jameses, her major interlocutors are continental thinkers of the twentieth century, especially the French: so, plenty of Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, Alain Badiou, Henri Bergson, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, Julia Kristeva, Paul de Man, Michel Foucault, Jean-Paul Sartre, Gilles Deleuze. All good, meaty stuff, and she’s not half bad on her use of the Germans, either: her lyrical uses of both Rainer Maria Rilke and Walter Benjamin are so good I can’t possibly do them justice here. Her command of these bodies of knowledge is astounding, and their intercessions into her analyses of Nabokov are all pertinent and well-chosen.

Like all these thinkers, Jöttkandt’s prose can be demanding. It’s also playful and incredibly fun to read. Often the joy isn’t so much in the matter of her argument, but in the fun she has stylistically in laying those arguments out. It’s real joie de vivre stuff, a little tiddle cup brimming with élan tiddles: this critic loves reading Nabokov. And she uses parody to her advantage. Critics like Naiman and Jöttkandt do so well as readers of Nabokov because they have embraced their own playfulness. What we have here is a hermeneutical preference for writing like you’re having fun, the implicit argument being that the end-product is self-evidently better and more interesting.

“Of course this approach to reading Nabokov necessarily also prompts a certain madness,” Jöttkandt admits, “one that is already familiar to readers of Joyce” (39). I’d hazard a fairly safe bet that Jöttkandt is thinking along the same lines as Derrida in his famous pair of Joyce articles: “Two Words for Joyce” (1984) and “Ulysses Gramophone” (1987).[12] It’s in these that Derrida identified a kind of textual Joyce haunting Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939), especially: a superhumanly knowledgeable author surrogate who has always already anticipated every possible reading, including yours. His clincher is this passage from the Wake:

Loud, hear us!

Loud, graciously hear us!

[…]

Loud, heap miseries upon us yet entwine our arts with laughters low!

Ha he hi ho hu.

Mummum.[13]

The laughter here, Derrida argues, is that of the textual author himself, the closest thing to order in all that Joycean chaos. As with Nabokov, the spectral Joyce lurks in some purgatorial space, suspended between his words and his reader. He chuckles to himself the whole time, a ceaseless and disquieting laughter aimed at language itself, and the reader’s feeble and predictable stabs at taming it.

The only way I can think of that might catch this kind of sadistically prescient spectral author is to absolutely embrace that “certain madness” so familiar to readers of Joyce, and Derrida’s Joyce, and hit him with something so quirky he couldn’t possibly see it coming.

Trolley to the End of Time.

At one point, Jöttkandt ushers her reader into a kind of repurposed trolley car like the one from Nabokov’s story “A Guide to Berlin” (1925), which she Doc Emmetts into a parody of a time machine. The only tracks this trolley runs on are the sprocket holes of a reel of film. She runs the film especially fast in her analysis of this story, speeding us and the trolley to the end of time itself:

The narrator’s proleptic nostalgia for the present, it turns out, is merely a front for a revised, “cinematic” understanding of literary transport. In the very same gesture with which it bestows the contemporary world with the otherworldly qualities of artefacts from a former time, literature unseats us from our location in the present. It is not the future but the now, it transpires, that is othered by literary perspective. Literature turns each of us into time travelers, temporal orphans whose tenure in the present expires before it can be lived. Silently betrayed by the rolling wheels of the trolley car, which hint at the reels of a projector, literature’s secret identity as a double agent of cinema is unmasked. The literary-cinematic tram’s “reels” wind and unwind the past and the future like reversible film spools, while the literary journey of a day in “Berlin” assumes the unmistakable air of a film screening directed by the “chitinous” hands of the ticketman. From these “thick” “rough” fingers, tickets are dispensed to the queuing crowds through a “special little window in the forward door.” (65)

Jöttkandt’s approach to reading Nabokov is among the maddest and most paranoid I’ve come across, and I mean that as a compliment. Deleuze and Félix Guattari would approve. She’s let her imagination run away with her. Good—that’s exactly what Nabokov’s about. It’s been a long time since I’ve read Nabokov scholarship as solidly imaginative as Jöttkandt’s. She’s supernaturally good at carving out her own idiosyncratic interpretative flow.

Jöttkandt visualises time cinematically, although I dare say the forces she projects on her literary-theoretical screen are older than the medium itself. Think Isaac Newton splitting white light into a whole colour spectrum, here. The loops of time come from long, stringy loops of tape, or “reversible film spools” that wind and unwind time itself. This is Jöttkandt’s critical cosmos: everything is film, probably including us. By speeding us in that trolley to the end of time, Jöttkandt ferries us to the end of filmic time. Depending on when you ask, this either resembles “the end of time” on film or the end of time in a film. In either case we’re dropped off right before the climax, at the most dramatically exciting part: the endgame.

Of the English-speaking nations, Australia probably has the clearest view onto the impending climate disaster. Rising sea-levels are pummeling our neighbours in the Pacific. And then there are the bushfires. Late 2019’s fire season was horrendous, and we’re hearing similar stories come out of places like California, Canada, and Greece. Ours burnt so much bush that koalas are an endangered species now. Then COVID hit and the news cycle moved on, understandably I guess, and obviously COVID was its own thing. For my money, though, Jöttkandt’s “endgame” trope has more to do with those reversible film spools.

When I say Jöttkandt fast-forwards our strangely-looping trolley car to the filmic equivalent of the end of times, I’m also talking about 31 December 1999, 11:59 p.m.: the turn of the millennium and “end of the world” from the point of view of pulpy science-fiction of the late twentieth century. Katheryn Bigalow’s cult movie Strange Days (1995) is a good example of a “futurist” film taking place in the time of the Millenium Bug. Even if the kind of 1990s “cyberpunk apocalypse” I’m talking about here isn’t identified in-text as being the turn of the millennium, somehow it was: such was the potency of Y2K at the time. Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge (2013) tapped into this same moment, too, and correctly identified 9/11 as the solution of continuity between last century and this one. There was no going back after that, every prior science-fictional apocalypse aged one-thousand years overnight, instead of just one-and-a-halfish. And the end of the twentieth century was a kind of apocalypse for scholars of the twentieth century: Nabokov’s century.

In 8-bit video-game land, the “endgame”—the end of the game, the end of time—would be the final boss fight. In The Nabokov Effect, the final boss is the spectral Nabokov himself:

Reading in the endgame means following Nabokov onto the cinematic topology of the letter where the literary turns out to be continually in league with a principle of textual interference, a curving “bend sinister” that re-plasticizes the alphabet. For this Nabokov, the pull of narrative’s arc becomes a lever not for effecting closure but, by means of a cinematic re-set, for cross-wiring literature’s plot engines. The ensuing “Nabokov effect” is both an assault on classical teleological models, and an opening onto other forms of reading and listening, always latent in a certain psychoanalysis that never did die but merely went “global,” which is to say, spectral. (42-43)

This description amounts to a kind of “calling out” of the spectral Nabokov—calling him out by describing him and his hiding-place. This shady, voyeuristic spectral Nabokov has been given a perch, a kind of “room in the sky” like the demiurge at the start of Eraserhead (1977), wherein he pulls sweatily on mysterious-looking levers all day. It is indeed an assault on classical teleology because it gives body to something spectral and at least partially imaginary. By calling out this hallucination of Nabokov’s ghost, Jöttkandt has also brought him into being. This, in turn, ensures that the “Nabokov” who comes to meet her in this final boss battle, here at the endgame, is by definition even worse than her own worst nightmare because he has come to her in a fever dream (which is the only way this whole setup works).

Now, this kind of brazenly suicidal summoning ritual isn’t performed very often for a reason: it’s dangerous and you’ll die. The spectral Nabokov is everything Derrida said the spectral Joyce is, plus he admits to being a massive troll:

How do you rank yourself among writers (living) and of the immediate past?

I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket, which I would now like to trace in reply to your question.[14]

Seriously, Nabokov is credited (in a non-monetarily-binding sense, of course) as one of the prefigurers of the smiley-face emoticon: it’s on Wikipedia and everything. Jöttkandt is wagering that the guy who saw that coming saw other things coming too, including where we are all headed as both a species and a collective hallucination of a species (because of course we’re imaginary too, but that’s another matter).

The only time a demiurge has any motivation to leave the safety of his extrinsic hidey-hole is just before the world ends, turning up mere seconds from the end just to say “see ya losers!” before disappearing in a puff of smoke. That’s why we’ve been fast-forwarded all the way to the endgame in Jöttkandt’s book. It must be. Imaginatively fast-forwarding to the end of time is a way of flushing out the spectral Nabokov (who’s imaginary, remember). In such a setting one can conceivably ask him questions one doesn’t normally get to ask: “What if we are the last readers of Nabokov?” is implicit in Jöttkandt’s subtitle, “Reading in the Endgame”. And might there be anything Nabokov needs to say to us before we become extinct and he no longer has an audience? We live in terror of a future where books will probably outlive the living, piled up somewhere in the ruins of our buildings after whatever cinematic bomb-drop does away with us in the end. Books are a kind of life without life, exactly like a ghost. That’s part of the Nabokov Effect, actually: knowing that Nabokov will be around for much longer than you will be—than we will be—and also knowing that there’s nothing you can do about it.

But you can’t just expect cheeky spooks like the spectral Nabokov to give up all their answers without a fight: you have to play him for them. To what do you challenge the demiurge against a backdrop he invented, and how on earth do you win? Jöttkandt’s plan is foolhardy, so foolhardy it might just work: challenge Nabokov to an old-school, cinematic showdown. Weapon of choice?—cinema itself, cinematic parodies:

It is cinema that triggers the Nabokovian time machine, insofar as the cinematic offers an alternative perceptual-cognitive transport system for conveying the sensations that will form the basis of our understandings of space and time. (51)

Nabokov was a cinema-goer, although obviously that was long time ago. It’s likely that the texts which had the most influence on Nabokov during his time in Weimar Germany were films. This was the heyday of Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau. And let’s not forget his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on Lolita (1962). Jöttkandt chooses cinema precisely because Nabokov himself was so literate in it. She isn’t trying to outdo him at his own game, cinematic parodies, but to play her analysis right into Nabokov’s strengths and make him look as cool as possible. Here, look: she even gives him a kick-arse entrance:

Like a double-agent or false flag operation, this other Nabokov slides cinematically through the letter’s secret passages in the field of literature, in the process hollowing out the narrative forms the latter enlists as its vehicles—the genres and subgenres of the detective story, the romance, the lyrical poem, the short story. For this Nabokov, the entire project of reading and interpretation finds itself dissolving into a spectral graphematics. (38)

Much has been written on Nabokov and cinema: Nabokov’s Dark Cinema (1974) by Alfred Appel Jr., Nabokov at the Movies (2003) by Barbara Wyllie, Nabokov’s Cinematic Afterlife (2010) by Ewa Mazierska, Nabokov Noir (2022) by Luke Parker, for starters, along with too many individual articles and chapters to mention here. None of it is like this. Jöttkandt’s cinema is far more Deleuze and Slavoj Žižek than Siskell and Ebert or Margaret and David. It’s as if someone has walked into a classic cinematic stand-off against Nabokov’s ghost—the kind with lots of close-ups of twitching eyes and twitching fingers intercut to Ennio Morricone—with Cinema 1 (1983) in one holster and Cinema 2 (1985) in the other. Fantastic.

Parody

Or at least, that’s one way of looking at it. Another is that both author and subject in this case are extremely good at imaginative parodies of films you probably haven’t thought about in a while. Jöttkandt parodies movies like Nabokov parodies movies (especially in Bend Sinister). Televisual forms and tropes are hysterically present everywhere throughout Jöttkandt’s book, which impishly, dizzyingly bends itself all the way sinister with little send-ups of more recent genre fare than Nabokov knew about. Some are very silly indeed. My film nerd radar reckoned it picked up “’90s hacker movie” vibes at one point, and Matrix-style “bro what if?” fare as well, all achieved via similar means as above. This is literary criticism by way of lovingly-crafted parodies of the full available brow, high to low. There’s a fun running gag in one chapter that parodies Henry James’s love of italicising things for emphasis.

At one point I had to read a particular paragraph several times, trying to decide if the author is intentionally parodying a very specific kind of 1990s science-fictional TV where, at a certain part of every episode, egg-headed scientists with names like “Dr. Daniel Jackson” or “Dr. Rodney McKay”—doctors, aways doctors—scribble excitedly on whiteboards and use lots of kinetic-sounding bullshit-words to explain how they’re going to break physics this week to beat alien-monsters and stop the world from ending. Instead of slowing the pace right down and teaching a primetime audience authentically complicated theoretical physics, these scientists hit us with lots of funny little “nothing” phrases like “using the slipstream as a buffer,” “boost the warp stream,” “sublight energy,” “use your latest algorithm, Frohike!,” etc., to move us along as quickly as possible to the part at the end where things blow up again. I’m reasonably sure that this, or something very much like it, is what’s being parodied here:

What if, that is, literature and cinema could comprise a hybrid form that, jamming the core program that runs our perception of space and time, could overturn the limit we perceive as death? What Freud would call the “manifold content” of Ada’s incest motif turns out to be Nabokov’s cover for infiltrating the traditional categories of space and time with a hybrid form that will outwit the deaths underpinning both the literary fantasy (“desire”) and its cinematic other (“jouissance”). “Incest” here carries the metaphorical payload of a coupling of brother and sister arts, a cross-bred or, better, inbred form that freezes narrative’s temporality with the stasis of the cinematic image that cannot age. In the figures of the child lovers whose “premature spasms” shock time’s forward motion, Nabokov forestalls all coming of the future. (110)

“Hybrid form,” “jamming the core program,” “metaphorical payload, “shock time’s forward motion”? This is pure Stargate, pure Trek.

Jöttkandt finds an honest-to-god wormhole here in the first section of “A Guide to Berlin.” See if you can spot it:

In front of the house where I live a gigantic black pipe lies along the outer edge of the sidewalk. A couple of feet away, in the same file, lies another, then a third and a fourth—the street’s iron entrails, still idle, not yet lowered into the ground, deep under the asphalt. […] [A]n even stripe of fresh snow stretches along the upper side of each black pipe while up the interior slope at the very mouth of the pipe which is nearest to the turn of the tracks, the reflection of a still illumined tram sweeps up like bright-orange heat lightning. Today someone wrote “Otto” with his finger on the strip of virgin snow and I thought how beautifully that name, with its two soft o’s flanking the pair of gentle consonants, suited the silent layer of snow upon that pipe with its two orifices and its tacit tunnel.[15]

You didn’t spot it. Jöttkandt takes the “tacit tunnel” of the os in “Otto” and fashions it into a multidimensional portal in critical time and space:

in Otto’s multi-dimensional palindrome, word intersects with world through a profoundly different relation than that of reflection. Not so much mirror images as “obverse” sides of a non-orientable surface, word and world are connected by a homeomorphic equivalence, where previous divisions of interior and exterior are re-marked as a fold. Otto is not just a three-dimensional pun, it turns out, but a glitch in representational spacetime itself around whose single edge the dual realities of Nabokov’s worlds, one “literary” and the other “cinematic,” start to align. (64)

Fronting as simple reversibility, Otto’s multi-dimensional palindrome inscribes a wormhole, a rupture or tear in the representational fabric of the literary plane. In this respect, “Otto” stages what may be the earliest of the world-transgressing shifts that have been hailed as the hallmarks of Nabokov’s writing. (173n23)

Lest one think that Jöttkandt has been carried away beyond that which is relevant to the text, here is Nabokov describing literary time in terms of something very much like a wormhole too:

I confess I do not believe in time. I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip.[16]

Let visitors trip, indeed…

Flow

Nabokov discovered quite early in life that working on a piece of writing could plunge him into a kind of trance. The trance was more intense the closer he was to finishing something. Sometimes the trance was so strong that, when he describes it to us in Speak, Memory (1966), his younger self seems to slip in and out of different physical locations without noticing how he got there, as if he’s dropping in and out of consciousness, or between sleep and wakefulness:

On that couch I lay prone, in a kind of reptilian freeze, one arm dangling, so that my knuckles loosely touched the floral figures of the carpet. When next I came out of that trance, the greenish flora was still there, my arm was still dangling, but now I was prostrate on the edge of a rickety wharf, and the water lilies I touched were real, and the undulating plump shadows of alder foliage on the water—apotheosized inkblots, oversized amoebas—were rhythmically palpitating, extending and drawing in dark pseudopods, which, when contracted, would break at their rounded margins into elusive and fluid macules, and these would come together again to reshape the groping terminals. I relapsed into my private mist, and when I emerged again, the support of my extended body had become a low bench in the park, and the live shadows, among which my hand dipped, now moved on the ground, among violet tints instead of aqueous black and green.[17]

It’s as if there’s only a single affective thread connecting one scene to another: the touch of his dangling fingers against carpet, then water lilies, then a mysterious violet glow of no specified abode. The way the scene has been framed in fictional space is remarkable: young Vladimir has remained perfectly still, arm dangling lazily down beside him, as all the physical objects of one scene morph around him to form all the physical objects of another, and then another. We aren’t dealing in regular space and time anymore, we’re dealing in an entirely imaginary kind of space and time which can only really work in fiction or in madness. Weird objects ebb and flow in narrative space. Colours and textures break free of their initial bounds and float around each other in sensorial space, compounding into even stranger stuff than that with which we started: “aqueous black and green,” “apotheosized inkblots,” “oversized amoebas,” etc.

In her analysis of this passage, Jöttkandt takes these weird inky pools, the liquifying reductions, and the black and green prefigural blotches of Nabokov’s trances, and converts them into mesmerizing figures on her own cinema screen:

A liquifying reduction of the semblance, an inky pool which, in spreading, laps at the limits of the lyrical I, bleeds through the phantasmal narcissal scene of identification. It is not the polished mirror of poetic language that more or less faithfully reflects “life” in the Nabokovian poetics. Instead, “life” here seems to be embodied as strange shadowy “pseudopods”—literally, fake feet—that grope and poke at the world from beneath the screen-like surface of the water. In this alternative, “cinematic,” account of apperception, representation does not so much reflect as absorb and resorb. Another representational ontology swiftly takes over: of language as a sightless, denaturalizing, “original” or first “false” life that masquerades as the negative or obverse of figure but left to its own devices invariably reverts to prefigural blotches. (44)

Here Jöttkandt’s taken something already weird, spliced it up, run it back through the projector, and made it even weirder.

Wrapping up

It’s not all parody of course. Jöttkandt has a lovely, very thoughtful, very elegant way with words that reminds me of Baudrillard, Gaston Bachelard, and Georges Poulet. All are exceptionally good at carving out their own interpretative flow in ways that gently compel you to keep reading. There’s a beguiling liquescence to Jöttkandt’s words, with every topic, every analogy, every cataract of analysis welling up and flowing smoothly and naturally from a common source, such that her conclusions, particularly at the ends of each chapter, feel as dramatic and inevitable as the crashing of a dark blue wave.

Up until now Jöttkandt’s work on Nabokov has been published as shorter chapters or articles. I have enjoyed sounding out my own readings against earlier versions of these chapters for the better part of a decade, during which time she’s been working diligently to turn it all into a book. I remember reading a much earlier version of the chapter on “A Guide to Berlin” very early in my postgraduate career, when it was circulated to attendees in advance of a departmental seminar in the mid-2010s. That part shone just as brilliantly then as it does now. When I first read it a decade ago, I was entranced by Jöttkandt’s renderings of Berlin’s network of subterranean pipes. In her hands they become the pulsing nervous system of a living, breathing leviathan-city. It made me stop for the first time and pay attention to how strangely water behaves in Nabokov, and I never stopped. Even if I was never taught by Sigi Jöttkandt in a classroom setting—(different universities, different universes)—I’ve still learnt from her all the same. The Jöttkandt Effect is pure distilled imagination.

Despite his being highly represented when one asks a classful of undergraduate who their favourite writer is, and despite having gratefully adopted Nabokov’s first biographer Andrew Field, Australia has fallen behind a bit in the Nabokov world. There hasn’t been a major book-length study of Nabokov by an Australian since Field’s VN : The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov (1986). There have been dabblers, sure: theses, chapters, articles, etc., by isolated scholars here and there. But no major releases. So Jöttkandt’s book is nothing less a thunderous announcement: Australian Nabokov is back.