KIRBY BROWN

(CHEROKEE NATION)

Me and Hank: Travelling Cherokee

Modernity with My Grandad

When I was a kid, my sisters, cousins, and I used to spend countless hours at my grandma and grandpa’s home on Morrison Drive in Big Spring, Texas, the small West Texas town where I grew up. A modest, working-class home to a retired oil-field worker and a housewife-turned-beautician, their home was a gathering place for our family, a site of celebrations, laughter, love, good cooking, and better company. It was also a site of story and family history where my cousins Chuck, Amber, Kelly, and I often ended up in our grandpa’s lap as he rocked us in his LaZBoy chair, two of us on each arm, and regaled us with stories about growing up as a young Cherokee boy in northeast Oklahoma in what had once been the Cooweescoowee district of the Cherokee Nation. We loved spending hours and hours at his place listening to his stories, tracking what was for sale on the local “Swap Shop” on the radio, drinking weak coffee with too much cream and too much sugar (as he liked it), watching baseball or boxing on television, or piddling about in the yard with him, my grandma, my sisters, and our cousins. If, as Jeff Corntassel, Rose Stremlau, Daniel Justice, and others have written, Cherokee nationhood is first and foremost grounded in Cherokee family and the extended kinship relations that bind us together, then that house and that chair were epicenters of Cherokee nationhood for one family living, working, laughing, loving, and trying to make our way hundreds of miles from my grandpa’s Cherokee homelands (Fig. 1).[1]

Figure

1: My Grandpa, Henry

George “Hank” Starr and grandkids around his kitchen table,

ca.

1977. Courtesy of my mother, Sharon Starr Sneed.

Born on the 4th of July 1906, as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, “Hank” or “Hen,” as his friends and family called him, lived through one of the most disruptive periods of United States-Indian relations. Before his first birthday, United States allotment policies, dispossessive assimilation initiatives, and Oklahoma statehood dissolved his tribal nation, disrupted Cherokee cultural and kinship connections, and alienated many families’ relationships to land and place. No longer protected by their own laws and institutions, Cherokees confronted some of the most devastating social and economic hardships since the forced removal from their Southeastern homelands to Indian Territory just six decades earlier. Poverty became rampant. Economic marginalization and racial discrimination forced many Cherokees to seek opportunities elsewhere, leading to a massive outmigration of over 40% of the population across the first three decades of the twentieth century.[2] Dispossession—both “legal” and illegal—was endemic, leading to what Oklahoma historian Angie Debo termed “an orgy of plunder and exploitation probably unparalleled in American history.”[3] The implications of these histories are evident today. Of the 4.4 million acres under collective Cherokee control in 1906, the year of my grandad’s birth, only 109,104 acres remained in Cherokee hands as of 2009. And of the more than 430,000 enrolled Cherokee citizens, at least two-thirds live outside the political boundaries of the Cherokee Nation, and fewer than eight thousand speak the language fluently. In many ways, the first half of the twentieth century was, as Cherokee National Treasure Hastings Shade (tsigesv) has noted, a “dark age” in Cherokee history (Fig. 2).[4]

Figure 2: Starr family allotment near Rose, Oklahoma, ca. 1912-1913. From left to right: Margaret Parris Starr (mother), Johnanna Starr (baby sister), unidentified woman, Ada Starr (sister), Henry "Hank" Starr, Felix Starr (brother), Joseph Starr (father). Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

At the same time, the rise of petromodernity and the capacity to travel more quickly and over greater distances afforded my grandad and many of his generation a degree of social and physical mobility, economic opportunity, and security that rural farm life could never promise. This was especially true for a young Cherokee man with little formal education in an increasingly racist, white supremacist, and hostile Oklahoma. Setting out not for the romantic territories of Mark Twain’s West but for the rough and tumble oil fields of Kansas, Missouri, and, eventually, West Texas in the 1920s and ’30s, Hank met and married my grandmother and began a family. In good Cherokee fashion, he also found jobs for his brothers and his sisters’ husbands, and so was able not only to bring his Cherokee family to him, but also to perform his kinship obligations and responsibilities as an older brother by helping to provide economic stability and to maintain kinship connections with his relatives. Throughout this time, Grandad participated in the oil-field baseball leagues that cropped up in small towns across the country, went on leisure trips with friends and relatives to Mexico, spent a stint with his father-in-law and other Oklahoma Indians in the wartime shipyards of San Francisco, and hosted dozens of Cherokee friends and relatives making their way back and forth across the country through the “Crossroads of West Texas,” where he lived and worked.[5] Though he returned regularly to northeast Oklahoma throughout his life to visit family, friends, and extended relations, it was in West Texas where he made a home and where he is laid to rest next to his beloved wife, Geneva, and his son, Tony (Fig. 3).

Figure

3: Henry George Starr

and Geneva Faye Starr Headstone, Trinity Memorial Park,

Big Spring,

Texas. Author’s photo.

As he and others tell it, my grandad was at once incredibly charismatic, loving, and a dedicated son, brother, uncle, husband, and father, but also prone to bouts of depression, anger, fear, alcohol abuse, and violence. He lived a hard life and was not always someone you wanted to be around, particularly as a younger man. But by the time I knew him in his late 60s and into his 70s, he had put many of those demons to bed and was the funniest, warmest, most interesting (and mischievous!) grandpa a kid could have wished for. Though I only knew him for a small fraction of the life he lived—he walked on in February of 1984 when I was nine years old—it is through him and my great aunties and uncles, through my mom and her siblings and cousins, and through my sisters and my nieces and nephews, that I am most directly connected to Cherokee Nation and to Cherokee history (Fig. 4).

Figure

4: Me and my Grandpa

napping on the couch, ca. 1974/1975. It’s difficult to tell who

got

the best of whom. Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

While I have never published anything on my Grandpa Hank explicitly, I am realizing now that he is all over everything I have ever done and that I have always been writing about him in one way or another. It is this history and these relationships that continue to organize my ongoing work on Cherokee literary nationhood as well as more recent work in North American Indigenous modernisms. They also organize new research on my own family’s history and its commitment to honor Grandad’s life and legacy as a legitimate subject for scholarly inquiry and as an exercise in relational accountability. Informed by Choctaw writer LeAnne Howe’s concept of tribalography and by what Sac and Fox historian Donald Fixico, Dakota scholar Phil Deloria, and Ho-Chunk historian Amy Lonetree variously describe as “writing from home,” this essay is an early attempt to put Cherokee private and public spheres into conversation as a way to make sense of my grandad’s life, the histories and circumstances he inherited, and the paths he and his relatives were able to carve out for themselves and their families in a post-allotment, post-Oklahoma, yet distinctly Cherokee modernity.

Tribalography and Writing from Home

Articulated in two foundational essays from the late 1990s and early 2000s, and expanded by writers and scholars in the two decades since, LeAnne Howe’s concept of tribalography is at once a rhetorical space, a narrative form, a critical methodology, and a theoretical framework through which to represent and make sense of Indigenous pasts, presents, and futures.[6] In a 1999 essay for the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, Howe connects tribalography to the transformative power of story more broadly, writing that “Native stories are power. They create people. They author tribes.”[7] Leveraging a host of genres and forms, often collapsing narrative distinctions between past, present, and future across multiple geographies, settings, and narrative voices/perspectives, tribalography works to “connect everything to everything” in what Howe describes as “a sacred third act” with the power to transform understandings of the past, conditions in the present, and possibilities for the future. Howe more explicitly captures these dynamics in a 2002 follow-up essay, in which she explains:

Native stories, no matter what form they take (novel, poem, drama, memoir, film, history), seem to pull all the elements together of the storyteller’s tribe, meaning the people, the land, and multiple characters and all their manifestations and revelations, and connect these in past, present, and future milieus (present and future milieus mean non-Indians). I have tried to show that tribalography comes from the Native propensity for bringing things together, for making consensus, and for symbiotically connecting one thing to another.[8]

In Howe’s Choctaw-specific tribalographic work, these elements emerge in a variety of ways: in the way she eschews linear time for a more spiral temporality in which characters, actions, and events repeatedly intersect and overlap across space and time; in the multiple geographies and homelands across which her work moves; in the polyvocal and multi-perspectival structure of her oeuvre; in the juxtaposition and bleeding of multiple genres and forms into and out of one another; and in the insistence on documenting the complicated histories that stitch peoples, places, and experiences together in a vast web of transhistorical relationships and responsibilities. As Joseph Bauerkemper observes, tribalography offers writers and scholars a model through which “to encounter and understand Native story, writing, and performance of the entangled past, present, and future” and, in doing so, “to reveal the ways in which Native narratives and knowledges fundamentally enable readers and writers to imagine otherwise.”[9]

More than a critical description of contemporary Indigenous rhetorical, cultural, and literary forms, tribalography’s formal and structural elements carry important intellectual, theoretical, and political implications. In its affirmation of all genres, forms, and modes of expression and representation, tribalography celebrates the multiple and innovative ways Indigenous peoples have always exercised representational sovereignty and self-determination, while also refusing artificial (and often prejudicial) distinctions to determine quality, value, merit, and worth (written vs. oral, literary vs. popular, high vs. low, literature vs. lore, philosophy vs. tradition, etc.). Rather, Howe consistently uses “story, history, and theory as interchangeable words because the difference in their usage is artificially constructed to privilege writing over speaking” and to celebrate the genius of individual authorship over the collective knowledge of families, communities, and tribal nations.[10] “All histories are stories that are written down,” Howe reminds us: “The story you get depends on the point of view of the writer. At some point, histories are contextualized as fact, a theoretically loaded word. Facts change, but stories continually bring us into being.”

This distinction between academic “facts” and Indigenous “stories” is an important one, considering the social and cultural cache historically accorded the academy as disinterested and objective arbiter of authority and truth. In tribalography, academic scholarship is but one of many modes of expression that presents a certain kind of truth based upon its own disciplinary assumptions and methodologies. Story, on the other hand, is always changing, always innovating, always adapting. It takes up academic objects, methods, and knowledges and situates them in relation to other modes of thought and expression that ask different questions, begin with different assumptions, and seek alternative forms of truth that lead to different conclusions. By recovering the multiple modes, forms, and venues in which Indigenous peoples like my Grandpa Hank navigated and helped to produce the worlds in which they lived, tribalography rejects narrow settler frameworks of dispossession, loss, vanishing, and damage for those of Indigenous presence, agency, imagination, and desire—in whatever forms, locations, voices, venues, and contexts they might appear.[11]

Tribalography also refuses what Mark Rifkin calls linear “settler time” by recovering Indigenous temporalities—and narrative structures—through which “history” might be remade or reimagined.[12] Tribalography understands the past not as an overtdetermined explanation of present conditions, but as an archive of alternative choices, of pathways not taken, and of imaginative speculations of presents and futures freed from the weight of the settler-historical past. Writing of her own community’s attempts to resist the imposition of blood discourse and racial politics on the White Earth reservation in the early twentieth century, White Earth Anishinaabe scholar Jill Doerfler also notes tribalography’s capacity to push “beyond the ‘facts,’” of academic histories, to “enliven […] (hi)story,” and “to offer an alternative way of remembering the past” by turning to other sources and narrative/expressive forms.[13] Anishinaabe descendant scholar Carter Meland observes how tribalography, as “a way of seeing, reading, and writing,” implicates readers, viewers, and listeners—both Native and non-Native—in a process of historical accountability and contemporary imagination, inviting them into a “generative act of sharing and exchange […] where the potential of Native story and knowledge carry us toward a new coherence.”[14] In this reframing, Meland continues, “[t]ribalography is a process, not a theory. It is something you do more than something you name; it’s an action, not an ideology […] Tribalography is no-ism, and we find its beauty in its motion to story peoples together.”[15]

In its two-pronged commitment to critique ongoing settler-colonial violence and to center, through story, Indigenous histories, experiences, knowledges, and lifeways, Chickasaw Nation scholar Jodi Byrd identifies tribalography as

a powerful theoretical tool in reading counter against the stories the United States likes to tell about itself and others. It raises deep implications about how, when, and for whom stories are told […] tribalography is first and foremost a way of thinking through and with Indigenous presences and knowledges in order to “inform ourselves, and the non-Indian world, about who we are.”[16]

More than simple counter-narrative, tribalography begins with Indigenous presences and assumes Indigenous futures from the get-go. Individual testimonies, family histories, and local community holdings are valued equally against academic scholarship and archival materials held in institutions. By juxtaposing these resources against academic scholarship, tribalography forces us to reckon with the erasures, absences, and misrepresentations of settler knowledges and institutions while also elevating “unofficial” sites of knowledge and experience as crucial sites of knowledge about our relatives, families, and communities. Though Grandpa Hank and countless others like him are absent from journal articles, monographs, and institutional archives, he is ever-present in our family’s (hi)stories, photographs, memories, and experiences. In a very real way, we are the archive and stewards of his life and legacy. He lives because we remember.

To “do” tribalography, then, necessitates recovering the historical past in ways that honor our ethical and relational obligations to those who came before us and to future descendants not yet born. Doerfler sees this as a defining characteristic of tribalography in the way it “balanc[es] rights and responsibilities via a system of relationships” that “necessitate reciprocity.”[17] Tribalography’s insistence on making connections and bringing everything into relationship across space and time “encourages a culture of ethical standards and reciprocal obligations” which pushes scholars—both Native and non-Native—“to consider the possible impacts of their work and, therefore, consciously work towards the creation of a positive and decolonized future.”[18] In this framing, Indigenous cultures, knowledges, lifeways, and experiences are not simply objects of scholarly inquiry and intellectual exploration. They are—we are—fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, aunties and uncles, nieces and nephews, homelands and waters, lifeways and philosophies, ancestors and descendants of all shapes and stripes for whom academic and intellectual pursuits often have very real, material consequences. When scholars—both Native and non-Native—write about our nations and communities, they enter that tribalographic space of relationship, responsibility, and accountability.

The stakes of these relationships are perhaps nowhere more intense than when we “write from home” about our own families and ancestors, not only because they are not here to offer their take on our work (would that they were!), but also because they—the complicated lives they lived and the often impossible decisions they had to make—laid the path we walk today.[19] As Ohlone Costonoan-Esselen writer and scholar Deborah Miranda writes in the contexts of her own tribal memoir, “My ancestors, collectively, are the story-bridge that allows me to be here. I’m honored to be one of the bridges back to them, to their words and experiences.”[20] Cherokee Nations scholar Daniel Justice identifies a similar ethical obligation to the past that organizes much of Indigenous literature, an “embraiding of kinship and accountability” that understands “the dead as ancestors with continuing relationships with the living, and how such considerations give us guidance for thinking of our own work as future ancestors.”[21] “Without those ancestors, without their stories,” Justice explains, “there is nothing to carry forward—there is nothing to bring to future generations.”[22] For Miranda, Justice, and others, the relational and ethical imperatives of tribalographic work—whether in scholarly research, literary and cultural production, political activism, or the unseen, everyday acts that organize our lives—are always already embedded in an intergenerational context of responsibility and accountability, “a deeper set of significant relations” without which “there is nothing to transmit to those who come after.”[23] At its most powerful, tribalography encourages us to look to our ancestors, to honor their ongoing presence and influence in our lives so that they might teach us a little something about our own moment and guide us to futures we might not otherwise imagine. Grandpa Hank continues to meet his responsibilities as an ancestor because we look to his life and times for answers to pressing questions in our own. That we remember him is the relational space of tribalography. How we remember him, and the stakes of that remembering, is the ethical space of tribalography (Fig. 5).

Figure

5: My Grandpa and his

living siblings, July 1983. Front, left to right: sisters Ada Starr,

Louise Starr Porter, and Johnanna (John) Starr

Yandell. Back, left to right: younger

brother Jack Starr and Grandpa

Hank. Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

In its formal, methodological, theoretical, and ethical dynamics, tribalography situates Indigenous peoples in an ever-present moment of creation, of agency, of always becoming in relation to the pasts we have inherited, the presents we are currently negotiating, and the futures we are attempting to imagine into being. From this vantage point, and to borrow from White Earth writer and theorist Gerald Vizenor, tribalography exchanges settler tragedies of Indigenous elimination and loss for Indigenous comedies of family and community survivance.[24] Tribalography seeks, as Michi Saagiig Nishanaabe writer and thinker Leanne Simpson has written in other contexts, to “produce more life,” in whatever genres, forms, modes, voices, venues, times, or places are available to us.[25] In this, tribalography is both critical and creative, both theoretical and practical, committed at once to critiquing the ongoing dynamics of settler coloniality and to celebrating the expansive possibilities of Indigenous desire, imagination, resurgence, and futurity.[26]

It is in this spirit and with these commitments that I offer one entry point into my own Cherokee tribalography—part intellectual origin story, part literary and cultural history, and part family history and personal reminiscence grounded in memory, photography, and story—and, of course, my Grandpa Hank, for whom the “modern world” was not simply a series of oppressive forces and conditions acting on him from the outside, but also, at times, a rich site of opportunity, mobility, and expanded possibilities.

The Roots and Routes of Cherokee and Native American Modernities

I began to take up questions of Cherokee nationhood, peoplehood, family, history, and literary and intellectual production in my dissertation research, which was eventually expanded into my monograph, Stoking the Fire: Nationhood in Cherokee Writing, 1907–1970 (2018). Addressing numerous scholarly absences on work on this period, the book critically examines how four Cherokee writers negotiated the complicated politics of Cherokee nationhood between Oklahoma statehood in 1907 and tribal reorganization in the early 1970s. Writing in a historical moment when the idea of an “Indian nation” was widely considered a contradiction in terms, John Milton Oskison, Rachel Caroline Eaton, Rollie Lynn Riggs, and Ruth Muskrat Bronson turned to tribal histories and biographies; novels, short stories, and plays; and editorials and public addresses as alternative sites of self-representation, critique, and the ongoing production of a Cherokee national imaginary. Across revisionist westerns, academic histories, modernist drama, and non-fiction writing, Cherokee nationhood exists in these texts as both a concrete literary presence and a relational conceptual framework of kinship and peoplehood through which the past, present, and future of the nation are remembered, represented, and reimagined.

In addition to what I read as a resistant and proto-sovereigntist politics of the literature itself, I was also drawn to these writers and others from their generation because of the diverse cross-section of Cherokee history and experience they represent. As children of mixed-race, multicultural families like my own, these writers span the gamut of Cherokee culture, class, and politics—from Old Settlers and removal survivors to Southern sympathizers and antislavery nationalists, from subsistence farmers and large-scale industrialists to cultural resisters and allotment advocates. Children of both native Cherokees by blood and intermarried white citizens naturalized under Cherokee law, they lived or held relations both in tightly knit, rural, Cherokee-speaking communities of extended families and in more patriarchal, nuclear-oriented families in railroad, cattle, and oil boomtowns across the Nation. Raised in and around both traditional and acculturated Cherokee households, they were reared in both Cherokee- and English-speaking churches and were educated in Oklahoma and Cherokee public and private schools. They were also exposed to a vibrant social, political, and intellectual life that was articulated primarily, though not exclusively, through Cherokee social, cultural, political, and educational institutions, contexts that show up over and over again throughout their work.

While many Cherokees continued to work locally to hold their families and communities together in the wake of allotment and statehood, others like Eaton, Oskison, Riggs, and Bronson pursued educational and professional opportunities that took them increasingly away from their tribal national home. These travels inevitably brought them into relationship with other Indigenous intellectuals, writers, artists, educators, and activists working locally to defend their lifeways and homelands from ongoing violence and dispossession, and organizing regionally, nationally, and internationally to challenge popular attitudes about Indigenous people and to effect substantive changes in federal policy, education reform, land management, and other consequences of modernity impacting their communities and families.

Questions of self-representation and conscious engagements with discourses of modernity and progress were central to these projects, and Indigenous peoples approached these questions across multiple geographies, venues, genres, and forms. From conventional literary forms of autobiography, narrative, poetry, and drama, through public speeches, editorials, legal arguments, and Congressional testimonies, to emerging forms of performance, music, cinema, and radio, Indigenous peoples adopted and adapted to their own ends the modes of representation and discourse through which their lives, lands, and futures were being decided. As a growing body of scholarship demonstrates, they did so not as modernist primitives, romantically vanishing Indians, or tragic victims of civilization and progress, but as central contributors to and active co-creators of some of the most important political currents, aesthetic movements, and intellectual conversations of their time.[27]

Where we once might have framed Indigenous lives and literatures from the early twentieth century on a narrow spectrum between assimilationist resignation and accommodationist ambivalence, we now identify what James Cox characterizes as a diverse “political array” of commitments operating in tribally specific, trans-Indigenous, cosmopolitan, transnational, and global contexts.[28] This ever-growing archive has allowed us to better account for what Leech Lake Ojibwe scholar Scott Lyons terms the “actually existing Indian nations” we all come from—the diverse, complicated, at times contradictory ways Indigenous folks have engaged and represented ourselves and the multiple worlds in which we move.[29] As tribalography demands, this includes the stories we tell, not only in scholarly contexts, but also in the closely held archives of our family histories and in the intimate spaces of our everyday lives, experiences, and relationships. Lives, experiences, and relationships such as those of my Grandpa Hank.

Cherokee Births, White People’s Independence, and Indian Humor

One of my most indelible memories of my grandad is of a 4th of July celebration in the late 1970s. I must have been four or five years old, but we always spent the 4th with my grandma and grandpa because, as luck, fate, or cosmic irony would have it, my grandad was born on July 4, 1906, a year before the federal government unilaterally dissolved tribal nations in Indian Territory. Again, I had no idea of this history at the time or what effects it had had on my grandad and his family. All I knew was that everyone on the block, across town, hell, across the entire country seemed to be pretty excited it was my grandpa’s birthday. After hanging out all afternoon and into the evening with all our aunts, uncles, cousins, and extended family I found myself next to my grandad, as I often was, our bellies full of cake, homemade ice cream, and sweet iced tea as we watched my sisters and older cousins set off Black Cats, ignite Roman candles, and spell their names in the air with sparklers. As night set and the city fireworks show began to erupt from South Mountain (really a hill) facing my grandparents’ house, my grandad leaned over to me, pointed all around, and whispered, “You see all this, Kirby 2? It’s all for me, it’s all for your grandad. The whole country turns out every year to celebrate my birthday.”[30] I believed it without question. I mean, it made perfect sense to me. To know my grandad was to love him, to want to be around him, so of course everyone would celebrate him (Fig. 6)!

Figure

6: Grandpa Hank

celebrating his 77th birthday, July 1983.

Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

It would be years later that I would understand the layers of irony, resistance, and refusal embedded in that joke. What it must have been like growing up in a settler state carved out of the lands and institutions of your tribal nation. To be within living memory—indeed within living experience—of the dissolution of the Cherokee Nation, the breakup of the tribal estate, and massive losses of land and life. How with the stroke of a pen, Grandpa Hank went from being a citizen of a sovereign Indigenous nation to a marginalized ethnic and racial minority in his own homelands, the legacies of histories of forced removal and internal violence playing themselves out again under the guise of progressive racial uplift and “killing the Indian to save the man.” The irony of celebrating your birthday each year on the same day that marks the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence, an aspirational document so central to American ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness against the tyranny of the colonial British state on the one hand, and the ever-present threat of “merciless Indian savages” lurking about the frontier wilderness on the other. Savages like my Grandpa. Or my mom. Or me.

A hundred and forty years after Pequot writer William Apess excoriated his Boston audience for their own religious and philosophical hypocrisies declaiming Cherokee removal in the South while ignoring their own Indigenous eliminations, removals, and erasures at home; a decade after Vine Deloria, Jr. called Civil Rights-era Americans to account for their “sins”—both historic and ongoing—against Native peoples; and twenty years before Arnold Joseph took “white peoples’ independence” to task in the 1996 film Smoke Signals, my grandad, Henry Starr, was, in his own way, opening that space of critique within me, perhaps in the only way he knew how: through biting humor, raucous laughter, and a wide grin that likely belied clenched fists and a hardened heart.[31] Echoing celebrated African American rhetorician and activist Frederick Douglass, I wonder what to my grandpa was the 4th of July? Looking back now, forty-five years removed from those storied afternoons in the LaZBoy and armed by all I know of the contexts that informed the early decades of my grandad’s life, I appreciate those moments and understand all he must have seen as those fireworks lit up the West Texas summer sky.

Education, Discipline, and Getting into Good Trouble

Grandpa Hank never explicitly mentioned the histories of dispossession and loss that organized Cherokee and Native American life in the wake of allotment and statehood. But they are implicit in many of the stories he told about his life and about what it was like growing up in rural northeast Oklahoma before the family sold their allotments and moved “into town” to Claremore just east of Tulsa. Given that he was such a strong-willed, independent-minded trickster, it is perhaps not surprising that many of Grandpa’s childhood stories involved him getting into trouble—sometimes good, necessary trouble, sometimes not—and his various attempts either to get out of it or to get even (Fig. 7).

Figure

7: Rural school photo,

Rose, Oklahoma, ca. 1913. My grandpa Hank is on the bottom row,

second from left. It remains unclear whether the adult man in the

back is the “Jack”

of my grandpa’s stories. Courtesy of Sharon

Starr Sneed.

In one story, he told of a white couple (he made a point of identifying them as such)—Jack and Jennifer—who taught at the rural schoolhouse outside of Rose that he and his siblings attended. Looking back, they sounded like the kinds of young, naïve, progressive white saviors described by his contemporaries Zitkala-Ša, John Milton Oskison, John Joseph Mathews, and others.[32] You know the type: well-intentioned, good-hearted, kind, and generous, committed to enlightening young Indigenous minds and transforming the world in the process, but possessing little, if any, knowledge about the students under their charge or any sense of how quickly and radically their world had been transformed. I do not recall Grandad saying much about the day-to-day goings on in the classroom, just that he and his friends often got up to one prank or another, often at his teachers’ expense, which landed them on the wrong side of Jack and Jennifer’s scales of discipline and punishment.

After one such incident, the details of which escape me now, they were instructed to march out to the pasture near the schoolhouse grounds and select a “switch” the teachers would use to “correct” their behavior. While the other boys reluctantly shuttled out of class and began trying to figure out which tree and what size branch would inflict the least amount of damage to their young behinds, Grandad was having none of it. He said he bolted from school, ran home, and then played hooky for days afterward. After his parents found out what he had been doing, he was escorted back to school where Jack instructed my grandad to once again go to the pasture and pick out his instrument of punishment. After he returned, Grandpa Hank was marched to the front of the room and publicly “corrected” as an example to the rest of the class. This did not appear to have broken his spirit, though; in fact, it seems to have had the opposite effect.

As he told it, on the way home, my grandad and a couple of accomplices positioned themselves on a small, brush-covered ridge above the path that the teachers took on the way home from school. As they walked under my grandfather and his friends, the boys began hee-hawing like donkeys and yelling, “Wait the Jack for the Jenny! Wait the Jack for the Jenny,” a not-so-subtle comparison to farmhouse “jackasses” with lewd sexual undertones to boot. While this minor act of revenge was short-lived—their voices were easily identified and they were dealt with accordingly the following day—I remember Grandad laughing until he cried at how he had gotten “one up on those white teachers,” even if only for an instant. The whole story was an extended prelude to those two joyful acts of defiance, acts that brought him as much satisfaction and joy recalling them sixty-five or seventy years later as they did the day he performed them, maybe even more.

Of course, the contexts that placed him in that schoolhouse in the 1910s under the instruction of white, settler teachers make those acts of defiance all the more poignant. From the first mission schools established at Spring Place, Hiwasee Town, and Chickamauga in the early nineteenth century to the national school system authorized by the 1839 constitution in Indian Territory, the Cherokee Nation had long lent qualified support to formal education as a means of defending the Nation against assaults on its sovereignty and of equipping its young people with the knowledge and resources necessary to prosper in a modernizing political economy. While debates raged in town halls, district court houses, and the pages of Cherokee and Indian Territory newspapers over the means and ends of the educational system, there was widespread agreement that education was a central pillar of Cherokee sovereignty and self-determination. As a result, prior to statehood, the Cherokee Nation boasted one of the most extensive compulsory public education systems west of the Mississippi, serving thousands of Cherokee students across hundreds of towns and communities.[33]

Had my grandad been born a decade earlier, that school would have likely been one of dozens of rural Cherokee common schools, funded and operated by the Cherokee Nation. It would have likely been staffed by Cherokee teachers from local communities who had been educated and trained in the Male and Female Seminaries which the Nation built as a national priority shortly after the reestablishment of the government in the 1840s following the Trail of Tears. And it would likely have been responsive first and foremost to the Cherokee families and communities that it served, most of whom may well have been their relatives or extended kin.

Acts of resistance captured in stories such as my grandad’s, and like those documented at both reservation day schools and federally operated boarding schools across the country, weren’t simply the shenanigans of youth or the ill-conceived plans of mischievous young minds.[34] They can also be read as small, generative acts of refusal, to borrow from Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson, of the authority white Oklahomans assumed over Cherokee lives in the wake of allotment—a refusal to be disciplined into submission or to break under the weight of assimilation and white settler supremacy.[35] As I visualize that young Cherokee boy being publicly whipped by white hands but refusing to be silenced or broken, that boy who would become my Grandpa Hank and who still gained so much joy from telling that story decades later, I am both proud and profoundly humbled.

Homecomings, History, and Memory

While many of Grandpa’s stories index similar contexts of Cherokee life in the wake of allotment, they also demonstrate his profound love for his family—both immediate and extended—and his lifelong efforts to remain connected regardless of how a rapidly modernizing world began scattering them apart. Our summers were typically filled with family reunions on both sides of my family. Every year or two until my grandad’s death, we would make the ten-hour trek from West Texas to his hometown of Claremore, to visit his brothers, sisters, cousins, and extended kin in what he always referred to as the Cherokee Nation. Though often we saw each other only every other year, for those few days in the summer, it felt to me like we had been around each other our whole lives. Though I did not realize it then, these visits were more than just family reunions or returns home; they were opportunities for Grandad to reconnect with his homelands and his extended family, and to introduce his kids and grandkids to significant places and people in his life. Put differently, these visits to Cherokee Nation were crash courses in Cherokee and Starr family history that few of us realized we were getting at the time (Fig. 8).

Figure

8: Family visit to

Claremore, Oklahoma, July 1983. From left to right: My great

uncle Jack Starr, me, and my Grandpa Hank. Courtesy of Sharon Starr

Sneed.

One of the places Grandad always made sure that we spent a good chunk of time at was the Will Rogers Memorial—an archive, museum, and living history dedicated to the celebrated Cherokee humorist. At the height of his popularity in the 1920s and ’30s, Rogers was widely regarded as one of the most beloved and well-known Americans in the world. Though popularly known as a downhome “cowboy humorist” and political satirist, Rogers always celebrated his Cherokee heritage, often positioning it before and above his affiliations with Oklahoma or the United States: “My father was one-eighth Cherokee Indian and my mother was quarter-blood Cherokee,” Rogers once said. “I never got far enough in arithmetic to figure out how much injun that made me, but there’s nothing of which I am more proud.” Speaking a couple of decades into the allotment era, Rogers would also write, “I am a Cherokee and it’s the proudest little possession I ever hope to have.” Should folks fail to remember the wider history of the country they were from or laugh a little too easily, a little too comfortably, at his commentary, Rogers would occasionally remind them, “My people didn’t arrive on the Mayflower; they met the boat.”[36]

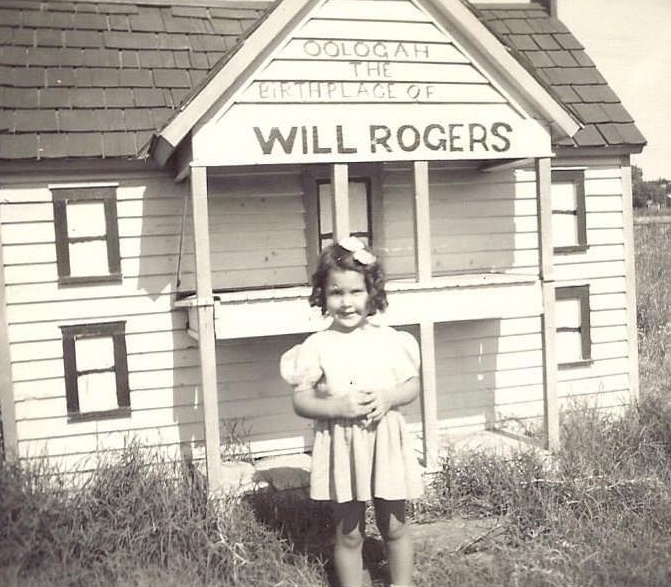

Figures 9, 10,

and 11: Starr family outside the Will Rogers Memorial, Claremore Oklahoma, ca. 1950s.

My mom, Sharon Starr Sneed, is pictured lower right. Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

At some point in our multiple visits to the memorial, which also typically involved a picnic of sandwiches, cold fried chicken, and iced tea out on the grounds, Grandad made sure to drive this point home: “That Will Rogers, he was one of the most famous Americans in the world. And he was Cherokee, Kirby 2.” These visits to the Rogers Memorial were not just something we did in our generation. They were a long-standing family tradition dating back to some of the earliest photos we have of the family, when my mom and her siblings were just kids (Figs. 9, 10, and 11). Like my grandma and grandpa’s home in Big Spring and the family homes we stayed at during our visits to Oklahoma, the Rogers Memorial was a gathering place, a Cherokee “hub” of sorts, a site of memory, memorialization, and ongoing Cherokee presence in a modern moment when the Cherokee Nation was still decades away from reorganizing, and later, when such reorganization was only in its infancy in my and my sisters’ generation.[37]

In many ways, the roots and routes that defined Rogers’s life—from hand on his father’s ranch to a failed attempt to establish his own ranching operation in South America, from trick roper and performer with Ziegfeld Follies to syndicated writer, actor, and radio personality—became an aspirational story for innumerable Cherokee families in Claremore, and of the wit, wisdom, humor, and resilience of the Cherokee Nation writ large. When I consider my Grandad’s penchant for pranks, comic timing, and raucous laughter—“Yeeeeee!” he used to exclaim after a good joke or humorous repartee—I cannot help but think of him in a long line of homegrown Cherokee and Indian Territory humorists like Rogers, Dewitt Clinton Duncan, Alexander Posey, and the countless others like my Grandad who will never find their way into books, journal articles, or popular memory, but who will forever be remembered in family and community histories and stories like ours.[38]

In addition to stops in and around Claremore, Grandpa also made sure that we made the day-trip to Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation, to visit the town square and historic courthouse, the oldest government building in Oklahoma, walk the grounds of the old Cherokee Female Seminary (now Northeastern State University), where many of our extended kin matriculated throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century until statehood in 1907, and visit the outdoor and indoor programming at the Cherokee Heritage Center just outside of town in Park Hill. Though the courthouse and university campus were not particularly memorable to me as a precocious young boy, I always looked forward to visits to the Heritage Center.

Growing up in West Texas and visiting Cherokee country only for a week or so in the summers, I never felt as connected to history, culture, and place as Grandad’s or my mother’s generations did. The Heritage Center was a place where even a light-skinned, young Cherokee boy could begin to put together the pieces of our larger history as a people and locate our own family within that story. Historical exhibits on the inside emphasized our resilience as a people after surviving and rebuilding following the Trail of Tears, the “Golden Age” of relative peace and prosperity leading into the destruction and devastation of the Civil War; how we rebuilt yet again and flourished despite constant pressures for our lands, resources, and institutions; and how we were then reorganizing and strengthening ourselves as a nation in our contemporary moment.

The center also highlighted Cherokee art and artisanship of all kinds that was actively being practiced and revitalized—from flint-knapping, bow and blow-gun making, and leatherworking in the “Traditional Village,” through long-standing practices of wood and soap-stone carving, weaving, beadworking, and pottery, to “modern” forms of abstract, impressionistic, and realist painting, photography, and printmaking. The juxtaposition of tradition and modernity, of past and present, of who we once were and who we were then as a people reflects what Cherokee scholar Joshua Nelson terms “progressive traditions,” innovations and adaptations made in response to contemporary circumstances but tethered always to longstanding lifeways, values, and cultural practices.[39] This orientation toward Cherokee history and culture made an impression on me and was one of the first times that I began to see the distinction between, on the one hand, the “Indians” of Saturday afternoon Westerns and “Keep America Beautiful” anti-litter campaigns and, on the other, the diverse Cherokee realities and histories that structured the stories of our family and the wider Cherokee Nation. Heritage, it turned out, was not just something you possessed via an abstract link to an ethnic or genetic past. It was something you did, something you lived, an ongoing connection to the Cherokee present through family, kinship, history, culture, and place that was being represented before us in our own words, on our own lands, and from our own perspectives.[40]

This connection of Cherokee pasts and presents was driven powerfully home for me at a 1983 celebration and fifty-year retrospective of the work of Cherokee artist Cecil Dick, my grandad’s cousin. At this time, both Grandad and Cecil were aging—Grandad was 77, Cecil was 68—though they still possessed that trademark Cherokee cantankerousness that made Rogers so famous. The retrospective was held at the Heritage Center and featured many of Cecil’s most recognizable works, along with a large mural of Cherokee history and culture that would hang in the W.W. Keeler Hospital in Tahlequah for years to come and which now hangs in the tribal complex. While I do not know whether Grandad appreciated art, I do remember that he loved Cecil and always made an effort to see him when he was back home.

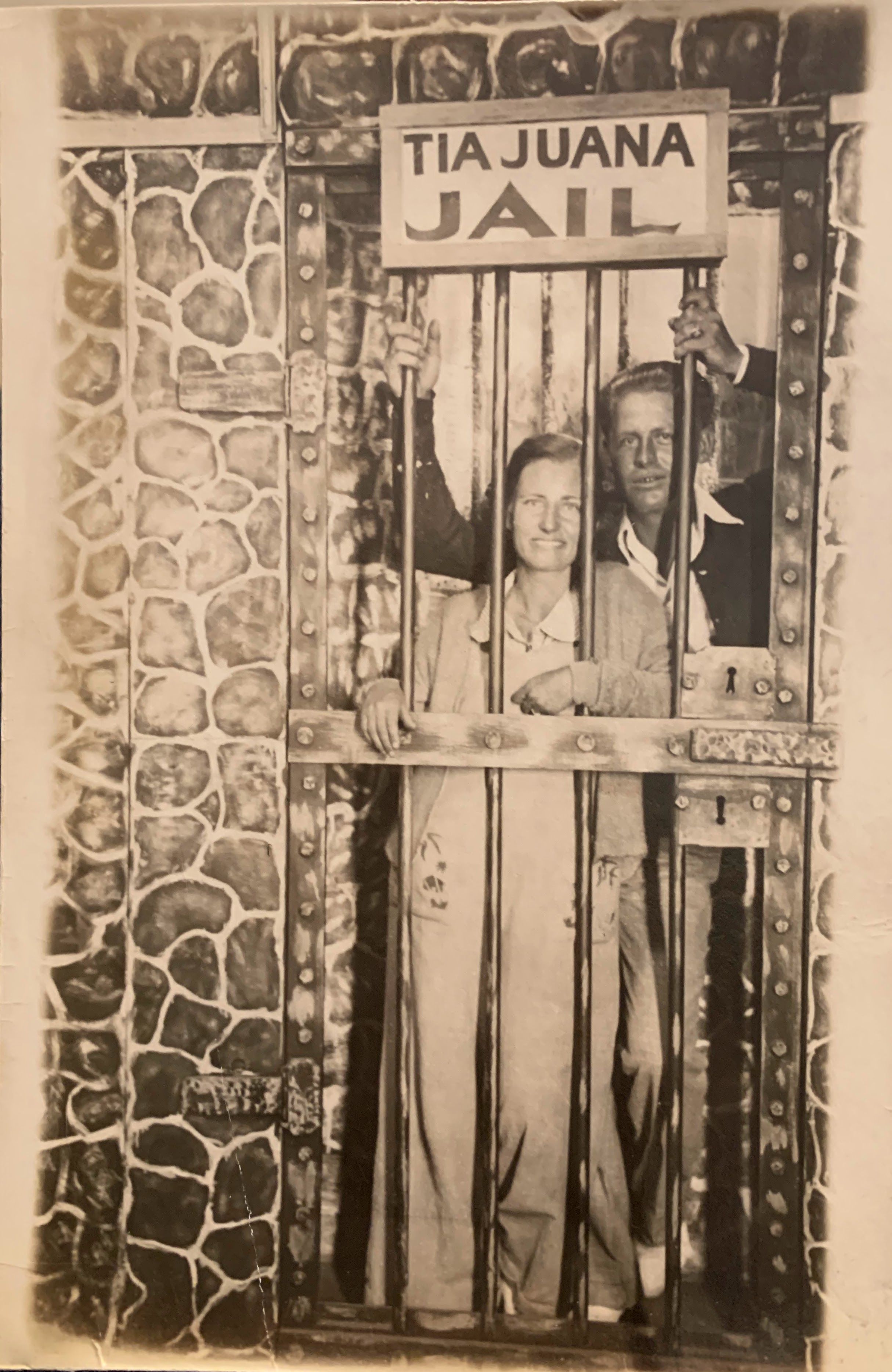

My mother also remembers Cecil and other relatives stopping by Grandad’s house in Big Spring on their way to Albuquerque, Santa Fe, or other places west where Cecil was traveling for art shows or to catch up with family. Two of my favorite photos from my Grandad’s albums are of him, his cousin Naomi Parris, and a handful of other friends and relatives at a bar in Tijuana sometime in the late 1920s or ’30s. The photo captures a group of dapper-dressed, young Cherokees having fun, enjoying one another’s company, and, if any of the other stories I have heard of my Grandad are true, likely getting into some trouble here and there (Figs. 12 and 13).

Figures 12

and 13: My Grandpa Hank, his cousin Naomi Parris, and other friends

and

relatives in Tijuana, Mexico, ca. 1920s or 1930s. Courtesy of

Sharon Starr Sneed.

I love these photos not only because they are some of the few we have of Grandad as a young man enjoying the prime of his early adulthood, but also because it signals just how mobile—physically and economically—many Cherokees were in this moment and how thoroughly embedded in the dynamics of early twentieth-century American modernity—travel, mobility, leisure, disposable income—they and other Indigenous people like them were. While many, informed by the film industry’s image of the feathered and leathered Plains Indian, might’ve considered my grandad and his relatives unexpected “anomalies” in such spaces and contexts, actual Indigenous people like Grandpa Hank, Cecil, Naomi, and thousands of others were busy leading lives, pursuing dreams, starting families, and maintaining their relationships to each other and to the peoples, places, and histories of their births.[41] Though often mispresented and erased in popular archives, scholarly studies, and public policy, materials and stories like these held in oral histories, family archives, photo albums, recorded conversations, and other local ephemera point to the diverse and “everyday” experiences, itineraries, and repertoires of relationship and resistance, of departures and returns, through which we have always structured our lives and communities.[42]

That it is also a photo of family—that central unit of Cherokee life and lifeways—speaks further to these dynamics. While our Nation was asleep during the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, our national families were still very much awake, alive, and dreaming futures for ourselves, our families, and our communities. As Cecil and Grandad caught up with each other that summer afternoon in the lobby of the Heritage Center, they were not just sharing memories and swapping stories. They were attesting to the creativity, strength, resilience, and brilliance of a generation of Cherokees who refused to let the consequences of United States settler modernity rip apart their most treasured relationships—those they maintained with each other (Fig. 14).[43]

Figure 14:

Starr family, ca. 1960s, location unknown.

Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.

Family, History, Place, and Story

These commitments to family, history, memory, and ongoing relationships were also evident in more intimate moments during our visits to northeast Oklahoma, when we always made time for afternoon trips to the family cemetery at Rose in the old Saline District of the Cherokee Nation. There, we would pay our respects to our Starr, Parris, Hopper, and Tehee ancestors, including Grandad’s mother and father, Margaret and Joe Carl; three of Grandad’s siblings who had passed on as children—Walter (1910), Carl (1913), and Felix (1916); and his Parris grandparents, Johnanna and Bud. We also made trips to cemeteries at Oak Grove, Pryor, Locust Grove, and Claremore, where many of Grandad’s sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, and extended family are laid to rest (Figs. 15, 16, 17, and 18).

Figures 15 and

16: Starr family resting places, Rose Cemetery, Rose, Oklahoma.

Top: Parents,

Margaret and Joe Carl. Bottom: brothers Walter, and

Carl. Author’s photos.

Figures 17 and

18: Starr family resting places, Rose Cemetery, Rose, Oklahoma.

Left: brother Felix. Right: Starr cousins visiting cemetery,

September 2023. Author’s photos.

In my own memory, these moments are not as well-defined as our time at our family’s homes or our trips to the Rogers Memorial, the Heritage Center, or Cecil’s retrospective. I remember being there, and we have photos of those trips my mother and others took, but the significance of those moments did not register at the time. Now I understand that Grandad made those trips not only to pay respects, but to connect his kids and grandkids to those places, to show us not just photos and stories, but also the physical, storied sites where our family lived, laughed, loved, struggled, grieved, survived, and built futures. As Tonawanda Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman reminds us, it is precisely these storied relationships to land, to specific places and geographies, that define both our historical and our landed relationships to each other. These storied, practiced, embodied relationships to place and to kin, renewed and reaffirmed each time we gather there, allow us to continue to determine for ourselves what family means.[44]

Our last trip to Claremore during my Grandad’s life was the summer before he walked on and I cannot help but think now, in retrospect, that as he approached the end of his own life, he did not want us to forget from whom and from where we came, to lose touch with the people, places, and histories that animate our wider web of relations as a family and as Cherokees. Along with meeting Cecil in person, these trips to Claremore, to Tahlequah, and to the resting sites of our family and kin were early anchors, along with my grandad, to my own relationship to Cherokee family, history, and community.

The more I revisit these photos and family documents; the more I share stories with my Mom, my sisters, my Auntie, my cousins, and others; and the more I reflect on my grandad and the work my mom and her generation have done to continue his and his family’s legacy in our own lives, the more I realize how formative, foundational, and influential he and those moments were for me. They are elements not only of my individual and familial origin story, but also of my academic, intellectual, and professional origin story. And they are the stories that continue to hold our family together, to connect us to each other, to our homelands, to our ancestors, and to the generations to come—including the precious ones we have recently welcomed into these stories (Osiyo Hudson Reed, Grayden Robert, Swayzie Reece, Stevie Lennon, and Tatum Starr!). I cannot help but think these little ones are the ones my Grandad and his generation, and the countless generations before, imagined as they were daring to desire and to dream their own Cherokee futures into being. To paraphrase a widely shared maxim across Indian Country—We are the futures our ancestors imagined (Figs. 19 and 20).

Figures 19 and

20: Starr reunions during Cherokee National Holiday, 2018 and 2022.

Courtesy of Ronda Rutledge, author’s sister.

As I draw this essay to a close and as I continue to work with and through these and countless other stories, I do so not just to better understand in an academic context the times and circumstances in which Grandad lived and their impact on his life. I take up and steward these stories, to paraphrase Daniel Justice, as a responsible descendant and future ancestor to hold him close to me, to give me inspiration and strength, to remember the histories and legacies to which I am accountable, and to remind me of the power of family, memory, story, and place to make sense of our past, to hold us together in the present, and to imagine where, who, and what we want to be for ourselves and for those who come after.[45]

Though Grandpa Hank did not live to see the Cherokee Nation grow and thrive into the resurgent nation it is today, and while he was not able to meet his great- and great-great-grandchildren in this life, I imagine him somewhere in the Nightlands surrounded by family and friends, proud of his nation and glad in heart to see his family still connected to one another, and probably sending us a hearty “Yeeeeee!” across the distance. I hear you, edudu. Gvgeyu’i. Donadagohv’i (Fig. 21).[46]

Figure 21: Me

and my Grandpa Hank, ca. 1978, Big Spring, Texas.

Courtesy of Sharon Starr Sneed.