CAI LYONS

“hibiscus in your dark hair”: Mary Swanzy

in American Samoa, 1924

In 1924, after spending six months in Honolulu, the Dublin-born artist Mary Swanzy (1882–1978) travelled to American Samoa. During her three months on the islands, the artist created a body of work unique in Irish art history, one considered a “counterpoint” to the work of Paul Gauguin and a “new model of representation.”[1] Born in 1882 into a Protestant professional-class family, Swanzy was well educated and part of a generation of Irish women artists pivotal to the development of modern art in Ireland in the early twentieth century.[2] At the time she travelled to Hawai’i and American Samoa, Swanzy was a committed and peripatetic landscape artist who transformed sites into artworks and whose core professional behaviour was exhibiting these artworks to garner sales.[3] This transformation of site into sight is evoked in the following exchange between Swanzy and her peer, mentor, and friend, Sarah Purser (1848–1943). In a letter from Dublin in November 1923, Purser imagined Swanzy, then staying with family in Honolulu, with “hibiscus in [her] dark hair painting orange natives with splay feet in between green landscapes.”[4] In the summer of 1924, Swanzy wrote back to Purser that

It will be sad to say goodbye to this perfect climate and beauty […] Don’t you feel that you want to go to Java? That is the place I imagine would suit me very nicely for painting, or the West Indies. I feel a “draw” towards tropical “scenes.” […] I think I would like Java [the] best.[5]

Swanzy was an artist in search of new motifs, whose desires to travel and to pursue a professional career as a landscape artist were inseparable. She imagined Java as a place of fantasy, a landscape formed of “tropical ‘scenes.’” The tropics conjure images of exotic (non-European, non-British) plants and animals, of a place free from modernity and industrialization, its identity in the European mind dependent upon specific visual representations. The expectation of the tropical—as exotic and unspoilt, a paradise free from modernization—corresponds with specific visual motifs—of palm trees, white sands, coconuts, and beautiful, often topless or partially clothed, women.

Purser’s imagined description and Swanzy’s own perception of “tropical ‘scenes’” represent modes of imaging and imagining enmeshed in colonial and imperial utopian fantasies of the tropical, where the body of the native signifies the tropical landscape. Many Euro-American visitors imagined the islands of the Pacific archipelago as a place of inspiration and regeneration, an escape from bourgeois modernity and industrial modernization. I argue that Swanzy was aware of this escapist imaging and referenced it visually through the painterly motif of the semi-clothed Samoan body. As I demonstrate further in this article, these imagined representations were painted for a specific Euro-American audience and were exhibited in Honolulu, California, Dublin, and Paris.

The paintings Swanzy produced in 1923 and 1924 have been described as experiments in the decorative effect of light on colour. Such descriptions aim to legitimize Swanzy’s canonical value as a modernist artist, while also viewing American Samoa through the lens of the white European artist. This implicit, universalizing gaze privileges a European perspective and closes off the ambiguity and tensions between cultures of modernity that underscore Swanzy’s colonial encounters. Swanzy’s Samoan works are informed by specific modes of imaging and imagining filtered through a racial lens, representations contingent on a “European vision,” a concept first outlined by Bernard Smith in 1960. Charting European perceptions of the Pacific, Smith argued that “seeing is conditioned by knowing” and explored the ways in which knowing and perceiving conditioned each other over time.[6] As Nicholas Thomas explains, “European vision” projects a unitary history, the implicit assumption of a shared space of action and meaning, of shared historical consciousness.[7]

In this article, I focus on that which—through this assumption of shared historical consciousness—has been overlooked or unseen: the tensions between, on the one hand, modes of imagining the “South Seas” as represented in Swanzy’s finished studio paintings and, on the other, the modernizing, colonizing forces of Euro-American industrialization represented in her preparatory en plein air sketches. Throughout this article, the term the “South Seas” is contained within quotation marks to acknowledge, textually, that the “South Seas” is in many ways a figment of Euro-American imagination and the “European vision” of the Pacific. As Jeffrey Geiger notes, the term might correspond to a real place, but it is also “a mythical and textually constructed space […] outside place and history.”[8] I am in agreement with Geiger’s use of the term, which suggests “a varied discourse of written and visual evocations of beaches, coral reefs, lagoons, coconut palms, and alluring native bodies, all holding the promise of sensual indulgence for western audiences.”[9] Such textual acknowledgement works in tandem with my deployment of a cross-cultural “double vision” to recognize tensions between the plural histories that underscore American Samoa.[10] Such “double vision” requires a disorientation of, or dislocation from, Euro-American perceptions and perspectives to investigate the ways in which the apparatuses of colonialism and modernity in American Samoa were compromised and contested. In turn, I ask specific questions about Swanzy’s time in American Samoa and the works she produced, to analyze, first, how her representations of indigenous peoples were mobilized as professional output to generate sales and, second, the extent to which colonialism and modernity were reflected in her artistic output.

Colonial Ambiguities: La Maison Blanche and the “Honolulu Swanzys”

Swanzy’s identities as Irish and as a British citizen, and her travel from one colonial space to another, throw up an unresolved ambivalence in her depictions of Hawai’i and, later, American Samoa. Swanzy occupied a paradoxical position, as colonized and colonizer: the Ireland she grew up in was a colony of the British Empire, yet her religion aligned her with the colonizer. She was a member of the Protestant professional class, and her father was Sir Henry Rosborough Swanzy, a notable ophthalmic surgeon and former President of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.[11] Although never wealthy, Swanzy’s family was of means, and the artist was left with a small inheritance after the death of her father in 1913.[12] This classed position connected her to a common British identity, without her becoming English, and marked her as participatory in British imperialism. Importantly, Swanzy’s travels to Hawai’i and American Samoa relied on networks established by the British Empire, her occupation as a landscape artist, and her wealthy, colonial family in Honolulu. The artist lived with the Honolulu Swanzys in 1923 and 1924 in La Maison Blanche, “the big white house, right across [from] Alexander Field” in the suburbs of Manoa.[13]

A wealthy and well-established family in colonial Hawaiian society, the Swanzys gained their wealth through the colonization of indigenous lands and the exploitation of cheap labour in the sugar industry. Swanzy’s paternal uncle, Francis Mills (F. M.) Swanzy, moved to O’ahu, Hawai’i in December 1880, marrying Julie Judd seven years later.[14] By 1898, he was the managing director of the sugar industry firm Theo. H. Davies & Co., and the owner of several sugar plantations.[15] Theo H. Davies & Co. was one of the “Big Five,” the name given to a group of five sugar plantation corporations that wielded considerable power in Hawai’i during the early twentieth century, shaping both the political and geographical landscape.[16] By the time Swanzy arrived in the port of Honolulu, the sugar industry, of which her uncle had been a key leader, “had remolded the islands into a production machine that drew extensively on island soils, forests, waters, and its island residents.”[17] Colonial and capitalist enterprise also shaped Honolulu, as it primarily served the interests of the sugar plantations. It was the main hub of the islands’ business and economy, and a substantial number of Asian plantation workers lived there.[18] Honolulu was a cultivated, colonial space, as subtly represented in Swanzy’s Honolulu Garden (Fig. 1).

The painting depicts a landscaped garden, with trees deliberately placed to create shaded pathways and a combination of native and cultivated plants amongst their trunks. It subtly highlights colonial structures of segregation and contact and the perceived right to own, shape, and subjugate conquered territory into domestic spaces. Honolulu was drastically and forcefully reshaped by colonial modernity and capitalist technology to support the mechanisms and machinations of the sugar industry. In this painting, the native flora is regulated and ordered, obscuring the violence of this colonial expansion and modernization.

Figure 1. Mary Swanzy, Honolulu

Garden (ca. 1923–1924). Collection & image

© Hugh Lane Gallery (Reg.1491). © The Estate of Mary Swanzy.

Very shortly after her arrival, it appears, Swanzy was not content with Hawai’i: Purser commented that a friend “brought me word […] that you were disappointed with the place for painting and climate.”[19] Ordered and controlled by the sugar industry, transformed by American colonial administration and capitalist economic expansion, Hawai’i was a different place than the artist might have imagined. While it did offer new contacts and encounters, these were structured by the racialized hierarchies of Hawaiian society and an urban, modernized, colonized landscape. Searching for better “painting and climate” and more “tropical “scenes,” Swanzy left for American Samoa—or rather, the imagined and imaginary “South Seas.”

Swanzy’s Sketches in American Samoa: Naval Outpost or Tropical Landscape?

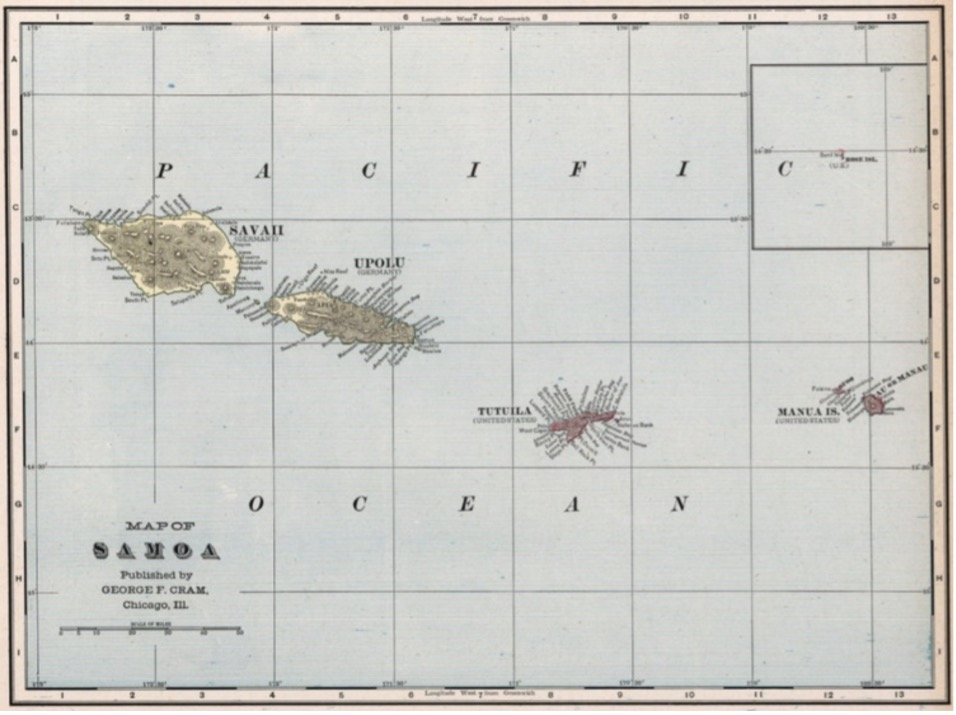

According to passenger manifestos and mentions in local newspapers, Swanzy departed Honolulu on 10 March 1924 on the SS Sonoma.[20] She likely arrived at Pago Pago harbour on or about 17 March.[21] The Samoan archipelago at the time of Swanzy’s visit was a fluid society and culture, but colonially and artificially divided between Western Samoa, under New Zealand administration, and American Samoa, which included the inhabited islands of Tutuila, Aunu‘u, and the Manu‘a Group (Fig. 2).[22] Such division was a result of the Tripartite Convention of 1899, which sought to resolve the recurring military conflict between the German Empire, Great Britain, and the United States of America as they competed for territorial ownership of the archipelago.[23] For the United States

Figure 2. George F. Cram, “Map

of Samoa,” in Cram’s Atlas of the World, Ancient

and Modern (Chicago: George

F. Cram, 1901), 271. David Rumsey Historical Map

Collection. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Navy, the Samoan archipelago was a space for imperial, economic, and strategic expansion, due in part to its privileged position between Hawai’i and Australia.[24] The establishment of the naval station at Pago Pago and of a coaling station to support the Navy’s expanding steamship fleet was the main objective, rather than government for Samoans or a colony for the United States.[25] By the 1920s, American Samoa was an autocracy under a naval commandant on frequent rotation, whose policies included the prohibition of land alienation and the recognition of indigenous customs in local administration; Samoan chiefs had advisory and judicial roles in government.[26] However, the reality of Navy colonial administration was less than positive, relying on intimidation tactics and prejudicial administrative policies, with often blatant displays of Naval favoritism. In the early 1920s, Police Chief Hunkin confessed to and was convicted of stealing government funds but was allowed to keep his job while paying back the money, whereas a critic of the government was stripped of his chiefly title and jailed for embezzlement.[27]

Yet the regulations of a naval autocracy had its benefits. The United States Navy closely regulated entry into the territory of American Samoa: a strict maritime quarantine meant there was a stark difference in how the territory managed the 1918–1919 flu pandemic compared with New Zealand-controlled Western Samoa.[28] There, the deathrate was one in five—a fifth of the total population—whereas American Samoa experienced zero deaths.[29] Many blamed this death toll on the New Zealand administrators and called for greater self-determination. By the time Swanzy arrived in American Samoa, Western Samoa was in the midst of a growing Mau (uprising against colonial administrative rule).[30] The Samoan archipelago was not a place free from modernity and industrialization. Once again, Swanzy was confronted with a landscape being transformed by colonizing and modernizing forces.

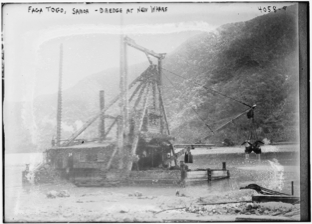

Figure 3. Faga Togo, Samoa—Dredge

at new wharf, c. 1915–1920, glass negative,

5 × 7 inches, George

Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs

Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-23279.

As the main American naval station in the Pacific—an important point in the colonial and imperial transport network between the United States and Australia, New Zealand, China, and Japan—Pago Pago harbour on the island of Tutuila was a place of intense capitalist industry and international trade. It was one of the largest natural harbours in the world, and its trade extended along the coastline into neighbouring villages. Swanzy arrived at a site of bustling colonial infrastructure, where dredges and wharfs built by hundreds of Samoans and other Pacific islanders were well established (as seen in Fig. 3). This was a complicated terrain of social and material interactions on reclaimed land: the coal sheds necessary to support the coaling station at Pago Pago were built on a man-made (Samoan-made) landfill with soil cut from nearby hills.[31] This terrain was the subject of several of Swanzy’s sketches when on Tutuila and there are also several extant drawings of warehouses along the wharf, likely in Pago Pago. In The Quay, Samoa (Fig. 4), boats without sails are moored close together, hiding the edge of the wharf. Warehouses occupy the background; the only hint of greenery is in the left upper corner.

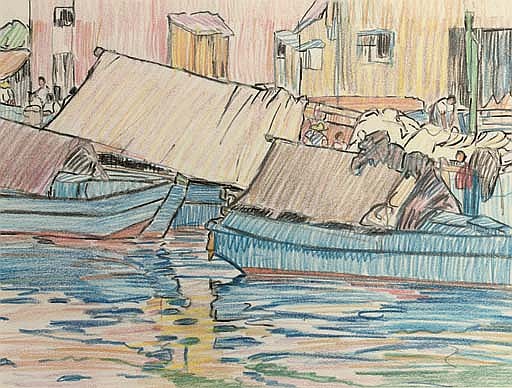

Figure 4. Mary Swanzy, The

Quay, Samoa, 1924, graphite and coloured pencils,

19 × 25 cm, Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images.

The cropped nature of the sketch, with boats coming into and leaving the boundaries of the page, emphasizes the intensity of this activity. And while the absence of sky or warehouse roofs focuses the attention of the viewer on the artist’s evocative depiction of swirling, mercurial waters, it also creates a sense of claustrophobia, of being hemmed in. A small group of figures can be seen by a doorway in the left corner. To the far right, a figure bends over and the head of another can be seen just below. Between the two tent-like covers, two more figures emerge; one wears a yellow straw hat. These are men who work outdoors, engaged in hard labour for capitalist and colonial industry. Swanzy also sketched several figure studies from the harbour, with fishermen and male dockhands at work, fishing, or reading. These sketches imply a gendered space, the public realm of working men. Absent any female figures or children, the sketches reveal the hierarchical and divided space of colonial power, the influence of Euro-American gender roles, and the inscription of binary social spheres. Men work outdoors, in the public domain, engaged in hard labour and industry. They wear loose-fitting shirts and trousers, and straw bonnets to protect them from the sun, rather than siapo (traditional barkcloth) or lavalavas.

Figure 5. Mary Swanzy, Samoan

Boats, 1924, graphite and coloured pencils on

paper, 19 × 25 cm. Image

credit: Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers.

A cropped composition and the sense of claustrophobia is detailed more effectively in another sketch (Fig. 5). The view of the harbour is enclosed and framed by the edge of the wharf, a moored boat, and the large overhanging eaves of a warehouse roof. The use of cool blue and grey implies that these buildings are made of imported steel, as was the case with the wharf in Pago Pago. The scene is empty of figures and the blue colouring evokes a more melancholic feel—the absence and aftermath of capitalist international trade. A pole covered in cloth diagonally bisects the frame of the sketch—is this a mast, a steering rod, or a central pole to drape the cloth over, as is evident in the previous sketch? Such boats were vastly different to the vaʻaalo—a plank-built canoe used for fishing—and the vaʻa tele or ʻalia—the double-hulled watercraft more traditionally used for longer journeys and transportation.[32] The absence of these canoes in any of Swanzy’s known sketches of Pago Pago harbour emphasizes the changing working practices of Samoans enforced by the naval autocracy. And this change is also present in the absence of workers. Dock and boat work was an alienating labour, fundamentally different to work in the service of one’s community—the household was the fundamental unit of production and the centre of Samoan life. This difference influenced workers’ willingness to work on the docks and boats and remain at work.

On the one hand, dock and boat work in the harbour was a new source of cash income for the Samoan populace, and by the turn of the twentieth century cash had been more fully integrated into the concept of reciprocal exchange which underpinned Samoan society. On the other hand, this cash income, provided by the Navy and its associated economy, was often necessary to pay the Navy-imposed customs duty on imports available in local shops or to purchase mea palagi, desirable manufactured foreign goods.[33] Such levies were the result of the capitalist drive to continuously generate revenue and increase profits, but the Samoan workforce was not without power. Taxation and corresponding fluctuations in prices proved to be a point of contestation between the Navy administration and the Samoan people, as increasing prices—inflation—did not align with Samoan exchange ethics.[34] Copra—the dried meat of the coconut—had been transformed into a cash crop and the naval autocracy in American Samoa depended on the taxes drawn from its sale. In protestation of naval mismanagement of these taxes, Samoans—many of whom were followers of the Mau—organized a copra boycott in the early 1920s and practically shut down the naval administration. Captain Waldo Evans, the Governor in Pago Pago from 1920 to 1922, quickly exonerated some of the accused protesters and created a more transparent Native Tax Fund. Reassured, the Mau followers resumed cutting copra soon thereafter.[35]

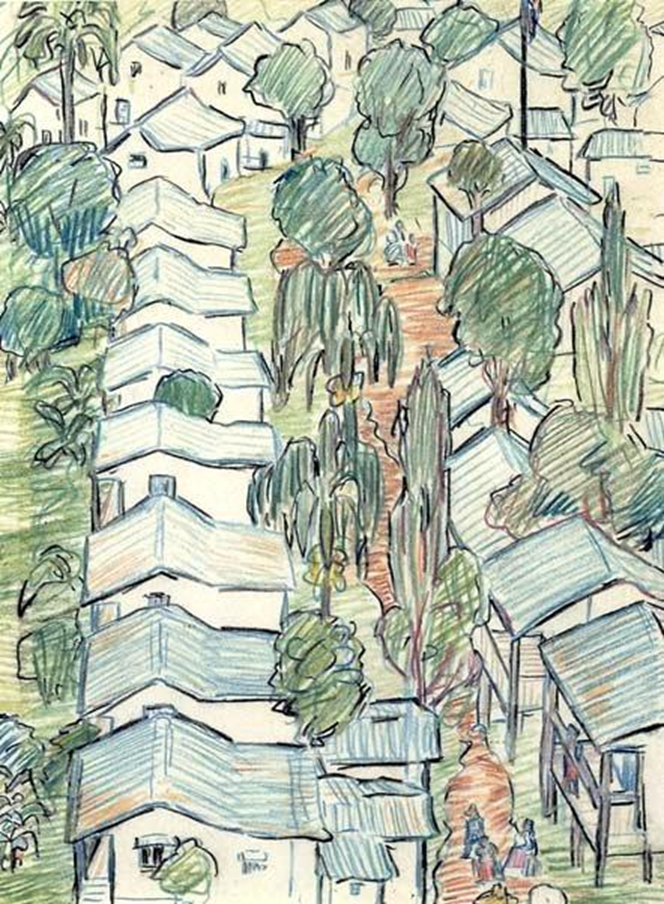

The Samoan workforce was essential to the prosperity of American Samoa, building its infrastructure and working the docks to transport the lucrative produce, copra, which the United States Navy taxed to maintain a cash flow. Taxes, licenses, and fines meant that the naval administration could, at the very least, maintain its colonial infrastructure and that Samoans had a new need for cash. This was a reciprocal, if often unbalanced, relationship, in which Samoans would work at the docks or produce more copra when the need for cash arose—as it often did. Missionary services also had to paid for and churches required donations. In one sketch, Swanzy draws a church set in a mountainous, rolling landscape. The artist’s choice to depict a church is important, as it references the long history of missionaries in the Pacific. By the 1920s, Christianity was firmly established in the Samoan archipelago and had transformed various aspects of Samoan life, including attire, education, textile production, and trade.[36] Some of Swanzy’s other sketches feature colonial houses and villages on Tutuila, representing infrastructure built by Samoan workers. This was not the “South Seas,” but a working landscape shaped by a Samoan modernity interacting with a colonial Euro-American modernity. One particular sketch, Village by the Sea (1924, graphite and coloured pencil on paper, 9.5 × 16.5 cm, private collection), shows a collection of small, square houses, raised on stilts, overlooking the sea. To the left, under an awning filled with purple and blue pencil strokes, is an automobile—a mea palagi. Samoan Village (Fig. 6) features more of these houses, some with porches, others with a second storey—more colonial infrastructure built by a Samoan and Pacific islander workforce. It is unlikely these houses were built for this workforce, however.

Figure 6. Mary Swanzy, Samoan

Village, graphite and coloured pencil on paper,

16.5 × 9.5 cm, private

collection. Photo © Peter Nahum at The Leicester

Galleries,

London / Bridgeman Images.

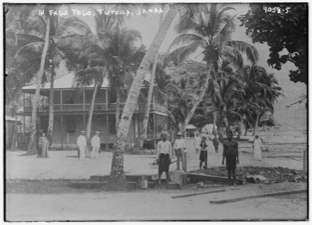

Figure 7. In Faga Togo,

Tutuila, Samoa, c. 1915–1920, glass negative, 5 × 7

inches, George Grantham

Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division,

LC-DIG-ggbain-23275.

The colonial architectural style of the houses in Swanzy’s sketches is recorded in a glass negative titled In Faga Togo, Tutuila, Samoa (Fig. 7), taken in 1915 for the Bain News Service, one of America’s earliest news picture agencies. In this image, a house with a wraparound, colonnaded porch sits behind a smattering of palm trees. In the foreground, Samoan men pause their work to stand still and pose for the photographer, with timber logs and mounds of dirt at their feet. To the left, nearer the house, are two members of the American Navy, dressed in Service Whites. Rather than a neutral, anthropological image of Fagatogo, this photograph captures the colonizing process through the literal construction of a domestic space for Euro-Americans. Swanzy’s sketches from Tutuila cannot be separated from this process in their depiction of the complicated interactions between Euro-American modernization, Samoan responses, and her own position as a professional landscape artist. The cropped composition of these sketches is reminiscent of the numerous photographs of American Samoa—and indeed, the entire Samoan archipelago—that proliferated during the early twentieth century. Max Quanchi has noted that photographs of “modern” Samoa, “characterised by capitalist economic expansion and benevolent colonial administration, with a school, governor’s residence, plantation, street scene, rural road or harbour-front”—as exemplified in Figures 3 and 7—were more prevalent than images of “ornately dressed taupou (chiefly virgins) and matai (chiefs) posing in traditional ceremonies and village settings.”[37] Swanzy’s sketches echo this first image of Tutuila, of capitalist economic expansion and colonial administration, of Samoan modern workscapes. They highlight the existence of cultural and colonial complexities—of clashing and complementary modernities—apparently absent from her paintings.

As Quanchi’s comment makes clear, the Samoan archipelago and its peoples were imaged in very particular ways. There was the image of American Samoa as a place of industry, progress, and American territorial, colonial expansion, that sat in direct contrast to the constructed image of the Samoan archipelago as a place of tropical paradise. This mythical paradise, Alison Nordström has argued, was represented through “manageable and marketable clichés which consistently presented Samoans as primitive types inhabiting an unchanging Eden that did not participate in the Western world of technology, progress and time.”[38] In search of this “unchanging Eden,” Swanzy travelled from the busy and industrious port of Pago Pago on Tutuila to the less populous Taʻū island, part of the Manu‘a Group.

Samoan Scene (1924): “the perfect climate and beauty”

It is unclear when precisely Swanzy made the journey to Taʻū, but it is likely that she spent several weeks there between April and late May of 1924. The artist produced numerous paintings, more than on Tutuila or in Hawai’i. While a catalogue raisonné does not exist, her exhibition history reveals she must have painted fifteen or more canvases: she had finally found the “perfect climate and beauty” necessary to paint “tropical ‘scenes.’”[39] It is clear Swanzy did not have access to standard painting supplies; her paintings were predominantly painted on canvas more reminiscent of burlap sacking than traditional linen. With a thicker weave often visibly distorted through heavy paint application and changing tensions, and a rough and unfinished quality, these paintings were likely executed en plein air. Such material and paint application can be seen in Banana Tree, Samoa (1924, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 55.9 cm, private collection).[40] Barely a year later, Margaret Mead would travel to Taʻū, where she conducted the ethnographic research that would culminate in Coming of Age: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation (1928). According to Mead, the community on this island was “much more primitive and unspoiled than any other part of Samoa.”[41]

Unlike Mead, Swanzy appears to have made no attempt to learn the Samoan language or engage with the community on Taʻū. Instead, she stayed at the home of the Navy Medical Corps Officer in charge of the single dispensary on the island.[42] From a distance, and from a position of difference, Swanzy painted women walking along single-track trails in the forest, men collecting coconuts or bananas, and in one striking image now known as Preparing the Meal (1924, oil on canvas, 61 x 50.8 cm., private collection), a woman preparing kava in a tanoa, the multi-legged bowl specific to this social and ceremonial ritual, with two female figures practicing the siva in the background.[43] Swanzy had a stronger interest in capturing and framing the landscape than engaging with Samoan culture and society; many of her painting from her time in Taʻū focus on the lush vegetation and the pattern of shadow on the forest floor, the figures appearing incidentally, merging into or emerging from the landscape.

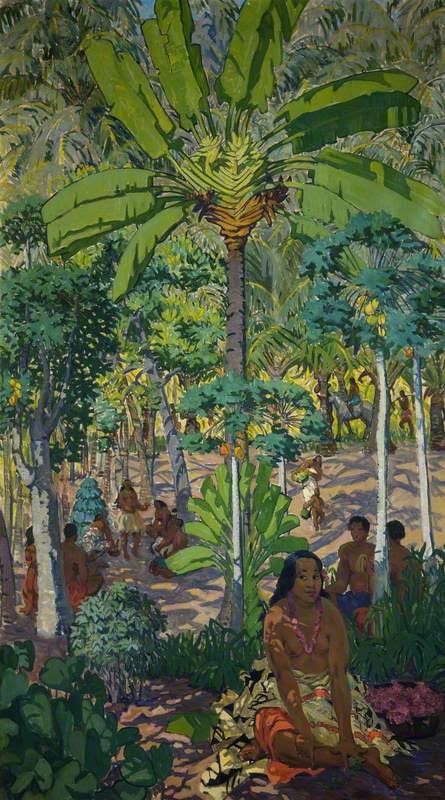

Figure 8. Mary Swanzy, Samoan

Scene, 1924, oil on canvas, 152.6 ×

91.5 cm.

Image credit: National Museums NI, © the artist’s estate.

Swanzy returned to Honolulu on June 17.[44] Barely five weeks later, she was exhibiting works described as “South Sea forest scenes” at the studio on the grounds of La Maison Blanche.[45] The artist herself commented that the exhibition was “a small [one] of my Samoan stuff.”[46] She placed several advertisements for her open exhibition in local newspapers, transforming her “green landscapes” populated with “orange natives with splayed feet” into marketable commodities orientated towards the Euro-American art market. In her personal correspondence, Swanzy noted that the exhibition received enough sales “to cover expenses.”[47] Significantly, a reviewer of the exhibition mentioned that Swanzy was “working on some larger canvasses [sic] embodying some of the compositions in the present group.”[48] This was Samoan Scene (Fig. 8), where almost each figure is a reproduction of or reference to the paintings produced in Taʻū. Behind the seated female figure, two male figures sit beneath two coconut palms, whose position echoes many of the figures in Swanzy’s drawings. Their lavalavas are bright blue and red, and one figure holds a bunch of bananas in their hand. To the right of the painting, along the tree line, a figure sits atop a horse or donkey and behind them, a male figure carries a pole across the shoulders. Below these figures, a female figure in a white lavalava braces a basket against her hip. On the left, a group of figures sits in a loose circle, their attention focused on a standing figure practicing the siva. To the right of this dancing figure, another seated figure leans over a bowl, recalling the ritual of kava preparation from Preparing the Meal. These figures can all be found in the paintings Swanzy produced in Taʻū. Consequently, Samoan Scene is an amalgamation and culmination of the artist’s travels, a statement of her skills as a landscape painter and proof of her “voyage” into the exotic and the tropical.

Figure 9. A Samoan woman

with leaves in her hair, albumen photoprint,

Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

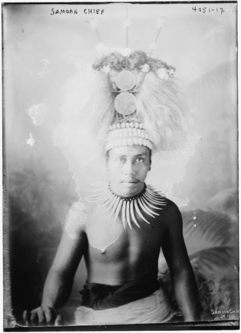

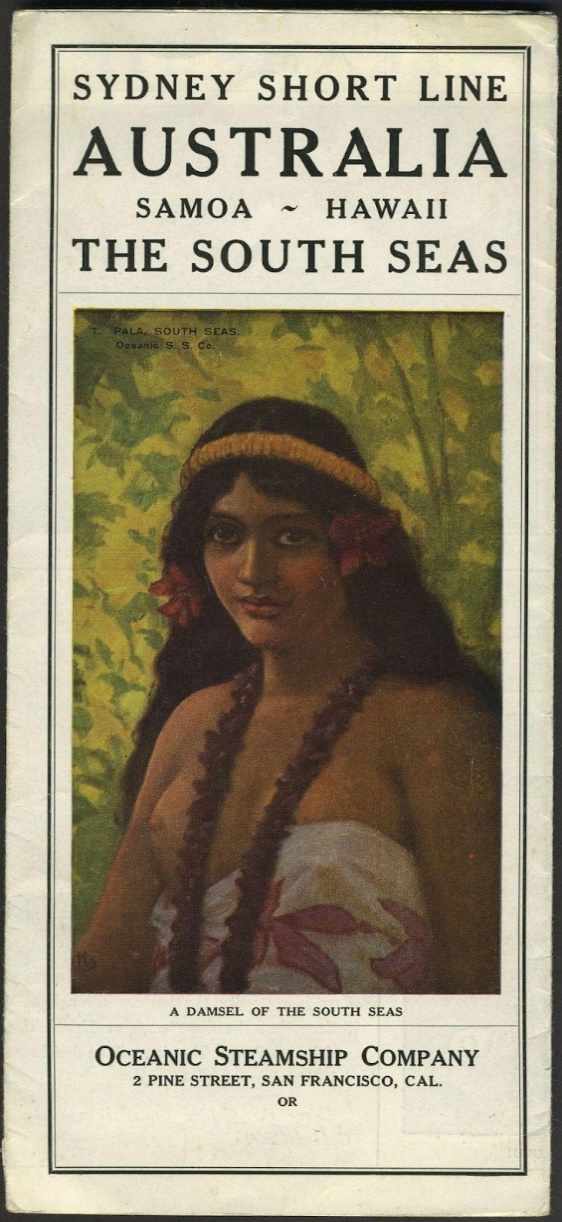

From the perspective of a unitary “European vision,” Samoan Scene represents the image of American Samoa as a place unspoilt by modernity and industrialization, where the partially clothed Polynesian female figure invites the viewer in. The painting (re)produces the expected colonial visual motifs of the “South Seas”: coconuts, palm trees, bananas, and partially clothed figures in traditional dress, their skin bronzed by the sun. This was the “South Seas” found in the studio portraits of the Samoan traditional “type,” of ornately dressed chiefs and partially clothed women, which were well-circulated by the 1900s and widely available as cartes postales (see Figs. 9 and 10). As Pago Pago was the key port for commercial and tourist ships alike, many of these cartes postales found an immediate global market amongst sailors and travellers: Swanzy would have seen these and similar images used as tourist promotional material. Advertisements for the Oceanic Steamship Company, which operated out of New York and San Francisco, featured images of partially clothed native women framed by palm fronds. In the advertisement for the Sydney Short Line (Fig. 11), a brown-skinned female figure gazes out at the viewer with large eyes and flushed cheeks. One breast is exposed, the other covered by what appears to be a lavalava, and there are flowers in the figure’s long curling hair; the similarities between the female figures in advertisement, carte postale, and painting are striking. Here is the sensual alluring semi-clothed Polynesian woman inviting the viewer into a tropical garden of Eden. Pointedly, the caption beneath the image in the advertisement reads “A Damsel of the South Seas.” In this visual context, Samoan Scene is a fully imagined landscape painted in the studio, populated with native figures as repeated “types” for a Euro-American audience—indigenous Samoan peoples transformed into a modernist artist’s professional output.

Figure 10. Samoan Chief,

c. 1915–20, glass negative, 5 × 7 inches, George

Grantham Bain Collection,

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division,

LC-DIG-ggbain-23232.

Yet such “tropical ‘scenes,’” when encountered with a “double vision” dislocated from the Euro-American place myth of the “South Seas,” reveal a more complicated picture. On plantations in Western Samoa under German and later New Zealand colonial administration, coconut trees were planted in straight lines, with clear divisions between the different plantation lands, in order to discipline workers and measure their progress.[49] Such divisions and rigid planting were absent in American Samoa, where there were almost no foreign-owned copra plantations: Samoans produced and sold only as many crops as they needed to support their community and earn cash when needed.[50] Maintaining the sustainable agricultural practice of household-centred farming meant Samoan communities could maintain their autonomy, and this autonomy meant they could resist the Navy’s desire to modernize and colonize the landscape through straight lines and road construction.[51] Swanzy’s en plein air paintings in American Samoa and the studio painting Samoan Scene subtly capture this resistance. Samoans enact long-standing labour practices based on co-operation and need, working with the existing landscape rather than shaping it to transport the copra cash crop to global markets.

Figure 11. N.G. Coutts, “A

Damsel of the South Seas,” Sydney Short Line Travel

Brochure, 1912. Oceanic

Steamship Company, San Francisco, California.

Image credit: Antipodean Books, Maps & Prints.

What is telling, however, is Swanzy’s own perception of the Samoans she painted. The artist could not dislocate herself from her own “European vision.” In an interview a few months after her visit, she complained that Samoans were “unwilling to pose. To stand still a few minutes meant work to them.”[52] Swanzy failed to comprehend the complementarity and reciprocal exchange ethics that underscored Samoan labour because she did not seek to participate in Samoan culture and society. Instead, there was a frustration with Samoans who were unwilling to pose and therefore thwarted her professional ambitions. This professional ambition cannot be understated, as it framed what, who, and where Swanzy painted. Objects sketched were not objects painted: the churches, colonnaded porches, colonial villages with an automobile, and busy harbours of her drawings did not signify the tropical “unchanging Eden” of the “South Seas.” Samoan Scene, when placed in juxtaposition to the sketches and in the context of Swanzy’s own motivation, highlights the artist’s selective gaze, informed by professional strategies and the motivation to exhibit: Samoan Scene, even in its subtle ambiguities, was explicitly produced for exhibition. It advertises the lure of exotic difference and the unknown, as much an advertisement as those Swanzy placed in the local papers in Honolulu, and reinscribing and perpetuating the “European vision” of American Samoa as a tropical paradise that underscored the production of cartes postales and touristic imagery.

Many Euro-American visitors envisioned the islands of the Pacific archipelago as isolated and unspoiled, as a place of inspiration and regeneration, or simply as an escape. In highlighting Swanzy’s decision to paint the visual motifs of a “South Seas” landscape rather than that of American colonial administration and modern industrialization, I argue that the artist was acutely aware of and engaged with this vision. Painted in the studio on the grounds of La Maison Blanche after her return to Honolulu, her Samoan Scene represents her attempt at imagining the “perfect climate and beauty” of the “South Seas,” rather than the colonial reality of Pago Pago harbour and the villages across Tutuila. Swanzy’s Samoan works were informed by specific modes of imaging and imagining filtered through a racial lens, representations of the “South Seas” contingent on a “European vision.”

Exhibiting “tropical ‘scenes’” in Paris

By September 1924, a few months after her return from American Samoa, Swanzy had a body of work ready for exhibition, one that demonstrated her accomplishments as a landscape artist and evoked the lure of exotic difference for the visual consumption of Euro-American bourgeois society—notably, a Parisian audience. During the 1920s and into the 1930s, Swanzy was strongly orientated towards the Parisian art market and the avant-garde.[53] In October 1925, Swanzy organised her first and only solo show in Paris at the prestigious Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. There, she exhibited fourteen paintings, including one called Scène Samoaene, but none of her sketches.[54] As noted above, colonnaded porches, churches, and busy harbours did not convey the same alluring paradisical and escapist fantasy as the partially clothed Polynesian female figure. As such, this exhibition must be viewed in the context of La Revue négre, the figure of Josephine Baker, and the contemporaneous craze of négrophilie.[55] An important aspect of négrophilie was the conflation of different racial and ethnic identities. As Petrine Archer-Straw argues, “‘Africa’ and ‘blackness’ were merely signifiers of the unknown [and] could be applied to any culture or race.”[56] The La Revue négre stage backdrop was heavily decorated with palm fronds, a visual motif meant to evoke a sense of untamed nature and the tropical, and a motif present in Swanzy’s paintings. A similar backdrop was chosen for the frontispiece of Swanzy’s exhibition catalogue: the partially clothed figure sits amongst coconut trees and palm fronds.

The merging of the undefined non-white topless female figure with exotic fruit and tropical foliage is recognised in a review of the exhibition:

Avec Mary Swanzy chez Bernheim-jeune, nous voici dans la Tropiques et quel rêve enchanteur que ces forêts inextricable où s’entremêlent bananiers et palmiers aux verts multiples à l’ombre desquels mulâtres et mulâtresses semblent vivre une idéale vie.[57]

The “mulâtres et mulâtresses” who live “une idéale vie” are inseparable from the banana and palm trees, affirming the affinity between untamed nature, the exotic primitive, and the colonial female subject. Such affinities are particularly unmistakable in Swanzy’s Samoan paintings, such as Samoan Scene. In calling these figures “mulâtres et mulâtresses,” the reviewer articulates the colourist discourses of race which frames Polynesian peoples as sexually desirable, exotic, non-threatening “primitives.” Swanzy’s Samoan figures live an idyllic life in the shade of banana and palm trees, revealing the nostalgic desire underpinning discourses of négrophilie and primitivism: a desire for pre-colonial subjects and objects that obscures the violent processes of colonization. The “mulâtres et mulâtresses” are “freed” from the anxieties and consumptive materialities of Euro-American modernity, bourgeois society, and industrial modernization. Such escapism would not have been facilitated by Swanzy’s sketches of an American Samoa transformed by capitalist economic expansion and colonial administration.

Instead, Swanzy transforms indigenous figures into signifiers of colonial and imperial utopian fantasies of the tropical. Such fantasies, such modes of imaging and imagining that refuse to move beyond a unitary history which others non-Western, non-European peoples, have continued into the twenty-first century. In 2014, the Irish art critic Brian Fallon wrote regarding Swanzy’s Samoan canvases that she “achieved some notable harmonies […] in her depictions of island women with their bright-coloured garments, softly brown limbs and (to us at least) asymmetrical faces.”[58] The comment “to us at least” is a clear indicator of the “European vision” of the colonial encounter. It emphasises the othering of the Samoan figures: the paintings of “island women” with brown limbs and “asymmetrical faces” depict people who are different to “us,” revealing both Fallon’s position as white, European, and Irish, and the assumption that the same can be said of his audience. Whiteness is an invisible medium through which Fallon and others encounter and view these works, and the medium through which Swanzy produced them. Whiteness and race are inescapable elements of Swanzy’s paintings from Hawai’i and American Samoa. Race is “something we see through […] rather than something we look at. It is a repertoire of cognitive and conceptual filters through which forms of human otherness are mediated.”[59] The Samoan figures are othered through this racial framing, transformed into objects “readymade for a painter to exploit” that signify the colonial fantasy of a tropical landscape to be viewed, displayed, and purchased.[60] And yet, as has been demonstrated, when dislocated from this “European vision,” there is a potential for a much richer, vibrant, and complicated interpretation of Swanzy’s Samoan artworks.

Conclusion: An Extraordinary Voyage?

The search for “tropical ‘scenes’” was an important strategy for Swanzy as she continued to position herself as a professional landscape painter in the early 1920s. Purser imagined her in the tropical landscape with “hibiscus in [her] dark hair,” a utopian fantasy where the artist could engage in her professional pursuit without distraction to paint “orange natives with splay feet in between green landscapes.” But while Swanzy’s exhibition at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune received more critical coverage than any other time she exhibited in Paris, no paintings were sold, and they remained tucked away in the artist’s London home studio for over four decades.[61] Swanzy was perhaps overly reliant on a specific mode of representation of the “South Seas.” The artist’s encounters in American Samoa laid bare her ambivalences towards colonial subjects and her own colonial ambiguities. Her Samoan paintings represent Euro-American modes of imaging and imagining American Samoa as the tropical landscape of the “South Seas.” These “tropical ‘scenes’,” when framed by Swanzy’s own ambitions, enforce the perceived right to transform conquered territory into imagined spaces of regeneration and rejuvenation for the Euro-American viewer. As with Honolulu Garden, the violence of colonial capitalist expansion and modernization is obscured.

But also obscured are the subtle traces in Swanzy’s artworks of Samoan modernity and its resistances, which only emerge when acknowledging and returning agency to the Samoan figures. Even in Swanzy’s idealised Samoan Scene, colonial modernity and Samoan resistances co-exist, uneasily and uncomfortably. When viewed alongside and contrasted with Swanzy’s sketches, and when placed in its historical context, the painting highlights the ambiguities of Samoan modernity—an Oceanian globality in which workers in Samoa created their own way to interact with and relate to the world. This Oceanic globality interacts and intersects and clashes with a colonial global modernity, representing the struggle to extend values of social reciprocity into the wider world.